Geopolitical regionalisation of the Baltic area: the essence and historical dynamics

- DOI

- 10.5922/2079-8555-2024-1-8

- Pages

- 141-158

Abstract

The article discusses a theoretical framework for investigating regionalisation and geopolitical regionalisation, employing the activity-geospatial approach. The main theoretical foci of this study are system-forming, or region-building, socio-geo-adaptation and geopolitical relations. The article examines various types of transboundary and transnational geopolitical regionalisation as manifestos of geopolitical relations. These types are categorised based on scale, functional area, historical and geographical characteristics, quality, legal status and geospatial features, placing particular emphasis on the Baltic region. An essential aspect of studying a region involves identifying and defining its spatial boundaries. Since determining the exact limits of the Baltic region remains problematic, this article examines various approaches to address this issue, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses, particularly in the context of geopolitical analysis. The concluding part of the article explores several centuries of the evolution of the Baltic Sea region, divided into historical geopolitical stages. It is highlighted that the geopolitical essence of the Baltic region was changing radically over time. Particular attention is paid to the current state of the Baltic regional geopolitical entity, which is classified as a conflict-ridden or confrontational geopolitical region in the ‘Eurasian arc of instability’ interpreted as a geopolitical macroregion.

Reference

Introduction

Geographical and social science — for example, regional and political studies — habitually use the terms ‘region’ and ‘regionalisation’, each with slightly different interpretations within these domains of knowledge. They became interdisciplinary, evolving to refer to a special type of social territorial processes and their results. At the same time, discipline-specific definitions and derivative terminology developed, often diverging significantly from previously established terms. Yet we believe that human geography has sufficient methodological and theoretical capacities to develop a single framework for analysing the process of regionalisation of society and its result — regions.

The Baltic region has garnered scholarly attention in Russia and beyond for over three decades since the territory integrates a variety of functional and historical layers encompassing geoecological, ethnocultural, social, geoeconomic, geostrategic and geopolitical aspects. Particularly, the literature delves into much-debated issues such as the definition and spatial delineation of the region. It also explores the primary features of the area’s historical geopolitical development and its current status. This study investigates geopolitical regionalisation in the Baltic region, seeking to identify the geo-spatial characteristics of this process from the standpoint of an activity-geospatial approach. Therefore, the objectives are to craft an interpretation of this approach suitable for regionalisation, to devise a typology of transboundary regions in view of the peculiarities of the Baltic space, and to define the Baltic region by delineating its borders, pinpointing the historical periods of its evolution, and describing its geopolitical development.

Geopolitical regionalisation of society: the theoretical aspect

Political geography studies encompass a wide range of topics and methodologies, reflecting the complex and multifaceted nature of political geography and geopolitics. Within Russian political geography, various theoretical approaches have emerged, aiming to provide theoretical frameworks for interpreting extensive empirical data.

The most influential of these concepts is the territorial-political organisation of society [1, p. 289—290], which represents a continued evolution of the more general concept of territorial organisation of society. From this perspective, the subject of political geography is the territorial-political organisation of society and its product — territorial-political systems existing both de jure and de facto, with ‘political-geographical sites’ as their basic units. This widely utilised concept is also the most operational as it links the theoretical subject to the observable geo-space (territory), which is interpreted through a mosaic of interconnected political geographical sites (a ‘site’ is visible, tangible and explorable).

There are alternative viewpoints as well. For example, below we will draw on the concept of geopolitical self-organisation of society rooted in the activity-centred geo-spatial approach, which weds ideas about society as a self-organising system [2] to the concept of geo-space. Geo-space is a system of natural, anthropogenic and humanitarian subspaces linked by relations of mutual adaptation (socio-geo-adaptational relations), which are established through interaction at the levels of information, energy and matter. Geo-space, being an essential dimension, necessary condition and principal environment for social activities and natural processes, imparts geo-space features to these activities and processes through geo-adaptational relations [3, p. 56—65].

Geo-space self-organisation of society and an aggregate of localised domestic and international historical conditions and factors launch a process of mutual adaptation between society and geo-space. As a result, specific systems of socio-geo-adaptational relations emerge that manifest themselves in the regional self-organisation of society, known as regionalisation. Regionalisation comprises region-building geo-adaptational relations between various actors: states, administrative units, international organisations, corporations, etc. These relations collectively shape regions as socio-geographical systems within geo-space.

Political geography explores a particular case of geo-adaptational relations, namely geopolitical relations, which develop between geo-spatial conditions and the political activity of society or individual political agents. Such relations can be viewed as basic units of research by both political geography and geopolitics, the latter serving as a comprehensive interdisciplinary area of knowledge and administration [2], [3, p. 47]. A geographical and political dimension is immanent in each such relation. This approach has a distinct advantage in terms of generalizing phenomena, as it enables the identification of the most abstract theoretical foundation. The notion of a political-geographical site can be understood as a complex of geopolitical relations, similar to how a geographical site is shaped by geographical relations. The entirety of geopolitical relations comprises geopolitical space. Therefore, stable localised relations of this kind can serve as the system foundation for geopolitical regions of various types.

As for the theoretical aspects, it is worth stressing the ambiguity of the scientific usage and cognitive role of the notions of ‘geopolitical regionalisation’ and ‘geopolitical region’ in geopolitics and human geography. Human geographers from St Petersburg, Russia, have recently proposed to adopt the activity-geospatial geo-spatial approach to solve this problem [4], [5]. They have identified ten of the most widely used types of ties that contribute to region-building, i. e. natural, economic, cultural, political, and other properties that Russian and international scholars employ to delineate geopolitical regions. Many of them are interpretations of Saul Cohen’s ideas as seen within different schemes of the world’s geopolitical zoning proposed by the researcher. The lack of a general geopolitics-informed theoretical framework for geopolitical regions has produced numerous interpretations of the phenomenon and various schemes of geopolitical regions (see, for example, [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]).

Drawing on the activity-geospatial geo-spatial approach to political geography, which is viewed as a science of geopolitical self-organisation of society, we adopt the theoretical definition of geopolitical region as a multiple-scale regional geopolitical system or a regional community of political actors involved in region-building geopolitical (geo-adaptational) relations that differ in form,<1> functional types and geo-spatial scale. This approach is highly conducive to the development of typologies of general regionalisation processes, geopolitical regionalisation processes and geopolitical regions. Helping identify different types of region-building relations, regionalisation processes and regions, functional differences in the activities of actors and geo-space properties for the basis of the social regionalisation typology. Of special interest are transboundary regions and, therefore, transboundary geo-adaptational and geopolitical relations [5]. The Baltic region, which is the focus of this study, instantiates a ‘testing ground’ of such typology, which will be considered below.

Two types of regions are distinguished based on the status of political actors and borders: supranational and national regions. The latter rarely have a geopolitical dimension. However, a large transboundary region may serve as a site for the development of small national subregions of socioeconomic or geocultural nature. Prominent examples are the depressed border districts, which illustrate the edge effect. Many similar studies have been conducted in Northwestern Russia — a territory often subsumed under the Baltic region.

Several levels of regionalisation are distinguished according to the geo-spatial scope of regionalisation. There are two applicable ranking methods: one based on the physical (metric) size of a territory (which identifies macro-, meso-, and micro-regions), and the other based on political features. At the supranational level, macro-regions may be socio-geographical or civilizational, or they may be bound together by a common sanctions policy. At the national level, examples include federal and economic districts, as observed in Russia and the US. Examples of meso-regions include subregions within Europe and Asia, territorial units of countries, and regions within Russia. Euroregions, Russia’s advanced development territories and countries’ lower-level territorial units, such as counties and communes, represent micro-regions. In political terms, transboundary regions are categorised into transnational regions, transboundary regions proper and cross-border regions. The term ‘transnational regions’ refers to areas spanning two or three countries either entirely or partially, irrespective of their size, with the Baltic region serving as a notable example. Transboundary regions proper encompass portions of neighbouring countries, whilst cross-border regions emerge from local-level collaborations, as seen in initiatives like the local border traffic regime that once facilitated transit between Poland and the Kaliningrad region [5], [13].

Based on their functions, i. e. types of activities performed by public agents, regions are categorised as follows:

1. Monofunctional (sectoral) regions. These include economical-geospatial or geoeconomic regions represented by regional international organisations (OECD, EAEU, VASAB [Vision and Strategies Around the Baltic Sea], etc.), socio-geospatial regions formed by the ILO, UNESCO, the Council of Europe, the Baltic University research and academic project, etc.; political-geo-spatial or geopolitical consolidated by NATO, the CST and bilateral treaties; geoecological regions formed by organisations such as HELCOM, which deal primarily with marine environment issues; religious-geo-spatial: civilisations, cultural-historical regions, etc.

2. Multifunctional (complex) regions shaped by the EU, the CIS, the CBSS and other associations

According to the legal status and governance regime, regions are categorised into de jure regions defined by regional international organisations (EU) and de facto regions (historical-geographical, civilizational, physiographical, factual, economic, etc.). The relationship between these concepts is more nuanced: a legal framework may exist for a structure that has never been implemented or has been put on hold; the opposite scenario is also possible. Moreover, a historical-cultural region can be defined legally but still lacks a governing body (see [5, p. 67, 71]).

Region-building relations allow dividing regions into two opposing categories:

1) regions of cooperation or integration — the EU, the EAEU, the Baltic region until 2014;

2) regions of conflict. These are transboundary grey zones characterised by sanctions, confrontation and peacemaking efforts, such as transboundary Kurdistan. This classification is, however, open to debate, as not all authors are willing to acknowledge the systematic nature and regional character of conflict-afflicted territories. Yet, conflictual relationships often lie at the core of a system, albeit in a negative sense [3, p. 108], [14]. Nevertheless, cooperative subregions of smaller scale may continue to exist within a conflict-ridden region, for example, through unions of allies within opposing political blocs. In this case, the region becomes polarised, as is happening with the Baltic region today. This situation should not be interpreted as a blending of the two categories, as they function at distinct structural levels within complex regions.

Based on historical-geographical features and trends, regions are classified into:

1. regions of integration proactively unite previously disjointed territories (the EAEU, Mercosur, Euroregions and the CIS before 2014). A particular case is integration for opposing common competitors. One can also speak of post-integration regionalisation, where a different, even more cohesive structure forms within the region (cf. the concept of ‘two-speed Europe’).

2. regions of disintegration, which either emerge from the collapse of a political system, as seen in the case of Britain’s Commonwealth of Nations, or experience a process of decline, often marked by a series of military conflicts.

3. post-conflict regions forming usually after wars, often forced. For example, the European Union emerged on post-war ruins as a region of integration.

Regions can be classified as follows according to types of regionalisation and geospatial characteristics:

1. As for the geospatial structure, it is more sensible not to identify individual types but to employ several polarised scales on which a region can be placed [5, p. 71]. Such scales are formed by two opposite types or notions. However, in real-world scenarios, regions rarely have characteristics placing them at one of the poles. The ‘monocentric — bipolar — polycentric’ gradation is an example of such a scale. Throughout its history, the Baltic region has moved several times along this scale in different directions. Another scale of interest in this case is ‘symmetric — asymmetric’. In terms of economic development and transport communication, the region is asymmetric, with Germany as an indisputable leader. From the geopolitical perspective, it is crucial to evaluate the region’s position on the ‘corridor/sector — belt/zone’ scale, particularly, in order to describe the geographical origins of transport corridors and energy projects or assess the degree of neighbourhood between countries and their parts. In the Baltic region, one can distinguish several zones of remoteness from the sea (see below for more details). The ‘core — periphery’ scale is probably the most popular with scholars of socio-geographical phenomena, particularly, regionalisation. For instance, models have been proposed for ‘periphery — periphery’, ‘core — core’ and ‘core — periphery’ interfaces. Finally, there is the ‘continuous/areal regions — dispersed/network region’ scales, which allows one to distinguish continuous economic zones and gravitation zones; transboundary network online communities and party structures. Overall, ongoing transboundary regionalisation creates new forms of regional spatial development, such as corridors, cores and growth triangles [13].

2. According to the material geo-spatial features, regions are classified into territorial, sub-territorial, land-water, land-air, land-space and integrated geo-spatial. Unlike most transboundary regions that are land-based, the Baltic region is one of the few that has formed around a body of water.

The Baltic region: points of discussion

The Baltic region began to emerge as a distinct territorial entity around the eponymous sea as early as the Middle Ages by virtue of favourable physiographical conditions: the sea itself, the ramified network of its catchment area, a single climate zone and flat shorelines, particularly in the south. From the physiographical perspective, the Circum-Baltic space provides a fertile substrate for the development of various forms of public life and self-organisation. This space existed before human settlement and the formation of local social entities. The term ‘Circum-Baltic’ was first proposed by Gleb Lebedev to describe the cultural-historical and civilizational context of the medieval period [15, p. 122].

Some Russian Scandinavists postulate the emergence of a ‘Baltic (maritime) civilization’ by the 8th century [see 15, p. 122, 129], although this assertion is debatable considering modern perspectives on local civilizations. If this conclusion is somewhat applicable to the maritime communities and cities along the coast during the Middle Ages, such as the 14th-century Hanseatic League of Cities, the territorial factor no longer dominates civilizational relations in the contemporary world. Baltic regional unity and identity, which undoubtedly endure, are subordinate to more comprehensive and significant phenomena. The Baltic Sea coast is home to at least two local civilizations, as described in Samuel Huntington’s model, with national and supranational (EU) identities dominating. Moreover, the Baltic and contemporary Western civilizations belong to different hierarchical levels. Therefore, the modern Baltic regional community is an inter-civilizational territorial phenomenon or a sub-civilization. Perhaps the historians and cultural scholars behind the Circum-Baltic concept overlooked the theoretical geographical aspect. Therefore, it might be advisable to focus the discussion on the formation of a geocultural, geoeconomic and geopolitical region, rather than on the emergence of a civilization. From the perspective of social geography, a region is not just a limited space but rather a cohesive or homogeneous entity, which can be transboundary [5] and even transcivilizational. Moreover, a geopolitical region can be united by either cooperative or conflictual relations, as abundantly evidenced throughout the history of the Baltic area.

Since the Baltic region emerged as a subject of academic study in the early 1990s, there has been significant debate surrounding the definition of its geographical boundaries. As one might expect, various perspectives have been proposed based on different approaches. The more the research problem leans towards a physiographical or geoecological approach, the clearer picture of the region’s borders is obtained by utilising physiographical criteria. The coastline of the Baltic Sea provides an indisputable reference point for a regional classification, as it is the primary factor shaping the region. However, there is still a point of contention as to where the waters, and consequently the sea coast, end in the area of the Danish Straits. ‘From the perspective of the BSR composition, it is expedient to draw its boundary between the Kattegat and the Skagerrak,’ and ‘[s]ometimes the Baltic Sea even includes the Skagerrak’ [16, p. 4, 5]. From a geopolitical standpoint, it is logical to include the Skagerrak in the region. The strait, along with the adjacent waterways, forms a unified geopolitical entity with the Baltic Sea, restricting access to it. The significance of the Baltic and Black Sea straits as gates to the respective water bodies was noted by Halford Mackinder in his strategic heartland model. He particularly stressed the role of the straits in the geopolitical zoning of Europe. According to the 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Baltic Sea, its jurisdictional area is limited by the parallel at 57 ° 44.43’ N (Article 1).

It is also worth noting the recurring proposals to consider the boundaries Baltic Sea’s catchment area as the borders of the region [15], [16], [17]. Whilst the catchment area offers an objective criterion similar to the coastline, its significance in region-building is limited due to its primarily geoecological role. Additionally, catchment areas may encompass uninhabited territories, further diminishing their relevance. In terms of geopolitics and the region’s public life, the Baltic Sea’s catchment area has only begun to gain significance in the last decades, and even then, in primarily the context of international efforts for coordinating environmental protection. However, the catchment area criterion has proven to be convenient for regional programmes and projects. Thus, the catchment area, albeit not a region-building factor in itself, becomes one due to its secondary, administrative and public nature.

Saint Petersburg, the Pskov, Kaliningrad and Novgorod regions, parts of Karelia and small parts of the Arkhangelsk, Murmansk and Tver regions meet this criterion. The region includes the entire territories of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, almost all of Poland, large parts of Sweden and Finland, over half of Denmark and almost half of Belarus, north-east Germany, small sections of Norway, Ukraine, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia (see the map scheme in [16, p. 10]). The Baltic University programme placed the Baltic region in approximately the same limits. Launched amid the euphoria of 1991 by Uppsala University, Sweden, this programme involved at one point universities from 14 countries [17, p. 17]. Today, the number of participating nations has reduced to ten. The catchment area of any sea is, however, heterogeneous, with the largest rivers playing the key geopolitical role. Lev Mechnikov (1888) went as far as associating the emergence of the earliest civilizations with the major historical rivers flowing through the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia [18].

It appears that the majority of authors deliberating on the region’s borders tend to overlook the fact that it was not the catchment area itself that has played a paramount geopolitical and geoeconomic role since ancient times, but rather its geopolitical component — the network of navigable rivers and, later, canals. The extent of inland waterways is smaller and sparser than the catchment area, with the majority of it situated in the southern part of the region.<2> For example, the catchment area includes part of Northern Norway, where no navigable route leads from the Baltic Sea. The network of navigable waterways has, of course, changed over time: some rivers that were fully navigable in ancient times may now only accommodate smaller boats, whilst others are plied by ships with significantly greater carrying capacity than those of centuries past. A significant portion of Finland falls within the catchment area. Yet, the country’s navigable inland waterways are linked to the sea only through the now-closed Saimaa Canal constructed in the mid-19th century. Although modern land transport can easily compensate for the lack of fully flowing river routes, it is not tied to the maritime region as such. Considering Baltic land transport networks would not differ much from analysing the transport connectivity in, for example, the Central European region.

Several navigable canals connect the Baltic Sea with the River Elbe, which flows through territories near the Baltic Sea coast and carries the region’s river traffic. However, according to the catchment basin principle, the Elbe is not part of the Baltic region. While this factor held significant importance during the Middle Ages due to the absence of canals, today, the Elbe and Oder rivers connect the Baltic region to the industrially developed regions of Germany.

During the Middle Ages, maritime and river routes served as crucial and irreplaceable means of communication over long distances. But as eras changed, so did the role of modes of transport. Maritime and river transport, particularly in coastal shipping, have diminished in significance since the advent of railways, motor vehicles and air transport. Recent studies into the transport connectivity of the Baltic region tend to focus on land and air transport, often within the framework of programmes like VASAB.<3> It is not surprising that projects for ring roads and railways have emerged. In the EU, approximately 40 % of freight is still transported by sea. What has remained virtually unchanged since the Middle Ages is the status of the Baltic Sea as a water basin open to international navigation; a similar status for the Danish straits was confirmed by an international treaty in 1857.

Therefore, the principal function of the Baltic Sea as the core of the Baltic region is the possibility to link any coastal state or city with any other coastal state or city without crossing third territories. It is worth noting that Pyotr Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky distinguished among spatial forms of geopolitical systems a circular or Mediterranean one [19]. In the Baltic, attempts to implement this form were made by Denmark, Sweden and, later, the EU. This structure not only offers economic advantages but also fosters the psychological perception of the Baltic space as a social entity (‘we are connected by the sea’). Therefore, the zone directly accessible by maritime and river communications constitutes the systemic core of the Baltic region.

Since this zone has a complex spatial form shaped by road networks, rivers and ports, 50 or 200-km wide coastal strips are often considered as such to simplify calculations [16, p. 12]. The entire zone surrounding the sea can be seen as one dimension of the Baltic region. This approach should not be classified as physiographical, as some authors suggest: one side of this zone is comprised of the coast, and the choice of 50 km as its width is conventional and based on the intensity of economic activities.

As we move away from the physiographical framework, delineating the boundaries of the Baltic region becomes increasingly complex. Historical, economic, cultural, sociological and political features of territories, or spaces, become factors at play. Then, legal criteria, although indirectly related to these features, are taken into account. Finally, the geopolitical approach integrates all these factors, viewing them through the lens of geopolitical interests and projects.

A straightforward approach would entail defining the Baltic region as encompassing countries and territories bordering the sea and reliant on it for their economic activities [17, p. 16]. Here, no matter what factors are considered, the political map takes precedence: the region’s components are either entire countries or their administrative units. Whilst this approach is undoubtedly effective for governance and administration purposes, it is primarily conceptual in nature. Additionally, the inclusion or exclusion of certain parts of countries, or entire countries themselves, is not always indisputable. For instance, when evaluating the effectiveness of traditional geopolitical approaches in interpreting contemporary Baltic issues, Kjell Engelbrekt includes in the region nine coastal states (excluding Norway), yet he does not offer a specific justification for this selection. A similar ‘coastal’ composition of the region can be seen in other international publications, but with Norway included.

A broader approach includes in the region countries and regions that do not directly border the Baltic Sea but are involved in international cooperation within Baltic development programmes, such as VASAB and Interreg. These two approaches result in the narrow and broad interpretations of the Baltic region, respectively. Here, the legal criteria are dominant: technically, the region’s countries can invite any neighbouring state to participate in Baltic programmes, thus classifying it as part of the Baltic region. A paradoxical situation may arise: a country that directly borders the Baltic Sea could withdraw from cooperation programmes and consequently no longer be considered part of the coastal region.

A ‘selective’ approach to understanding the composition of the Baltic region is seen in the EU’s Baltic Sea Strategy, where only EU members are categorised as states of the region, with Norway and Iceland viewed as desirable partners.<4>

Finally, in the broadest sense, the Baltic region can be expanded to constitute a Baltic regional geopolitical system, which includes not only the Baltic region in various interpretations but also geopolitical relations and external actors with significant geopolitical interests in the area [3, p. 84, 85]. These external factors include non-regional parts of the region’s major countries, for example, Russia and Germany. In this case, inclusion criteria become even more blurred, with a feasible one being participation as observers in regional international organisations, such as the Council of the Baltic Sea States. In the Council, 11 countries have or had this status: Belarus (until 2022), the UK, Hungary, Spain, Italy, Netherlands, Romania, Slovakia, United States, Ukraine, and France, which has applied for full membership and Iceland as a full member.

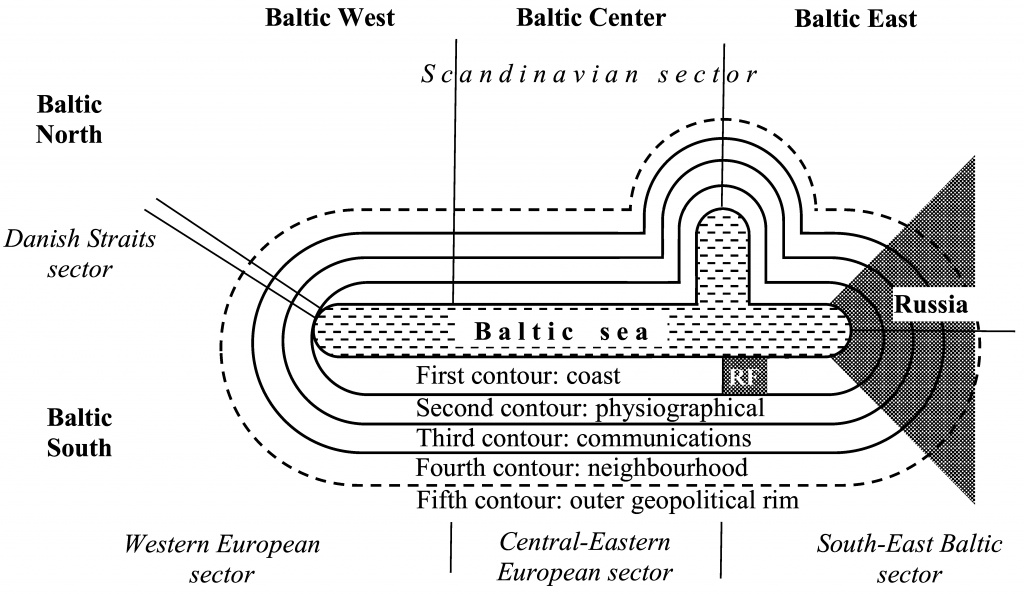

From a geopolitical standpoint, all the above delineation options do not exclude one another. Each of them merely suggests a focus on a particular type of geopolitical relation, highlighting it within the complex multidimensional structure of geopolitical space. Summarising these approaches, it is more appropriate to speak of the Baltic region having several geopolitical contours as zoning principles, rather than distinct demarcation variants (see Figure).

|

| 1 |

|

An idealised model of the Baltic region

|

|

|

I. Marine or coastal contour. It includes 50- and 200-kilometer coastal zones, parts of countries or entire smaller countries bordering the sea, as well as territorial waters and exclusive economic zones.

II. Physiographical contour. It includes, by definition, the sea itself and its catchment area. Other parameters may be utilised as well: the effect of the sea on the local climate of the features of the terrain.

III. Communications contour. It primarily encompasses inland waterways and a network of sea and river ports. It can also include rivers belonging to the basin of neighbouring seas but servicing the coastal contour and connected to the Baltic Sea by navigable canals. The busiest maritime routes should not be ignored either, nor should be other forms of contemporary transport communication: roads, railways and air routes, provided they have a regional character. Hence the interest in ring roads and routes along the coastlines. When examining this contour, it is essential to pay attention to the area of real economic influence of the coastal factor (cf. the delineation of a strip of constant width for contour I).

IV. Neighbourhood contour. It comprises territories of countries that do not directly border the sea but are either adjacent to coastal states or have territories included in contours II and III.

V. Geopolitical contour (regional geopolitical system complete with region-building geopolitical relations). It outlines a vast region encompassing all the above contours and relations with extra-regional players pursuing interests in the area.

Historical dynamics of the Baltic regional geopolitical system

It seems more reasonable to discuss the timeline of the geopolitical regionalisation from the perspective of historical dynamics within the global geopolitical system, of which the Baltic region is an integral component. This discussion should be based on a clear understanding of the historical types of geopolitical relations (geopolitical processes and their outcomes) throughout the system’s development. To assess the contemporary situation, it is particularly important to understand the specifics of these geopolitical relations during the capitalist and modern periods (Modern and Contemporary periods in historical terms). Here, special attention must be paid to differences in types and correlations of geopolitical processes, the role of actors involved and the resultant regional geopolitical structure.

During the Westphalian era (1648—1815), following the Thirty Years’ War and the Peace of Westphalia, religious and ethnic-driven geopolitical processes shaped the geopolitical trend towards state sovereignty. Four geopolitical subregions of a core-periphery type emerged, with the geopolitical poles in Sweden, Poland, Prussia and Russia (the Moscow State and the Russian Empire). Although the Westphalian era, like others, had its own internal structure, we will only mention general European geopolitical periods pertaining to the relevant international relations systems. For the Baltic region, several stages can be distinguished within these periods, which differ from the stages of geopolitical development observed in other regions of Europe. Among these stages are the stage of Russia’s heightened involvement in the Baltic geopolitical system (early 18th century) and the final transitional phase of geopolitical instability — the era of the Napoleonic Wars.

The Vienna era (1815—1914), which followed the Napoleonic Wars and the decisions of the Congress of Vienna, saw the gradual emergence of two geopolitical subregions with Prussia (from 1871 — Germany) and Russia as their respective poles. This process took place under the influence of imperial-state geopolitical and ethnic-riven geopolitical factors.

In the Versailles era of the 1920s—1930s, which began after the First World War and the introduction of the Versailles system of peace treaties, a bipolar Baltic regional structure emerged, with two principal geopolitical subregions — the Western (capitalist) and Eastern (socialist) ones. Germany constituted the geopolitical pole of the former, and the USSR of the latter.

The Potsdam era (1945-early 1990s), a product of World War II and the decisions of the Potsdam Conference, launched foundational geopolitical processes manifested in the confrontation between the capitalist and socialist systems. They shaped a bipolar structure with two opposing core-periphery geopolitical subregions of a generative type: the West Baltic (capitalist) and the East Baltic (socialist). West Germany, supported by Western allies, and the USSR became the integrative geopolitical poles in the Baltic space. The Baltic region underwent a military-political and geo-economic division, with territories aligning with NATO/Warsaw Pact or EU/Comecon. During this period, the Baltic region had a paramount geoeconomic role for the USSR: the share of the region’s countries in the bilateral trade of the Union amounted to 29 %. Although Poland and East Germany accounted for most of this percentage, West Germany and Finland were also notable trade partners [17, p. 19].

The Belovezha era (from the late 1980s / early 1990s to the present) is characterised by a geopolitical trend towards fragmentation of the Baltic region into geopolitical regional communities of different scales and different types — national, supranational, ethnic and other. Initially, foundational geopolitical and ethno-geopolitical processes manifested themselves in the collapse of the socialist system and its structures in Europe, the dissolution of the USSR and the formation in the Baltic space of ethnocentric post-socialist states undergoing a process of ‘Westernization’ occurring at different speeds across the area. This process involved reforms rooted in Western political, economic, and humanitarian technologies. For the first time, despite the ongoing divergence in geopolitical stances among states within pre-existing subregions, there was active development in economic, social, and humanitarian integration. This gave rise to new regional communities of various sizes known as cross-border cooperation regions (Euroregions and regions formed by the Interreg programme, the Council of the Baltic Sea States, the Helsinki Commission, VASAB and other initiatives). Over the past fifteen years, these processes brought to life Europe’s most successful ‘region of cooperation’. The Baltic case has been actively studied and promoted as a model for cross-border cooperation in other border regions (see [21], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]). Nonetheless, the relative importance of the region for Russia gradually decreased amid the expansion of the country’s trade geography. By 2014, the contribution of the Baltic region to Russia’s total bilateral trade had decreased to 18.5 %, with 8.9 % attributed to West Germany [17, p. 19]. From Russia’s perspective, a ‘Russia — Germany’ trans-Baltic geo-economic corridor formed in the region, the culmination of the process being the 2012 launch of the Nord Stream gas pipeline. At the same time, the region received fewer and fewer mentions in each new edition of Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept.

From the standpoint of the stability of geopolitical relations rooted in the geoeconomic reality and ensuring the success of the region, one can postulate the emergence of a new de facto regional cooperative geopolitical community in Europe — the Baltic geopolitical region. The region’s stable geopolitical relations of cooperation remained conspicuous in the vast space of the ‘Eurasian arc of instability’, which runs through several conflict regions in the post-Soviet space [14].

However, NATO’s enlargement, which has been a source of conflict since the late 1990s, the geopolitical fracture of Ukraine in 2014, marked by Crimea’s integration into Russia, and, since 2002, the special military operation has had negative geopolitical and geo-economic repercussions on the Baltic region and collective Europe as a whole. Initially, in 2014—2021, these adverse effects manifested themselves in restrictions and curtailments of mutually beneficial cross-border interactions, which resulted from the ‘sanctions geopolitics’ pursued by Western countries and the countermeasures taken by Russia and Belarus. In 2022, the collaborations came to an end, accompanied by the dissolution of previously established forms of cooperation that had fostered regional unity. In addition, new ‘collective’ instruments for dividing the Baltic region emerged, informed by an anti-Russian and anti-Belarusian sentiment. As a result, Russia had to announce its withdrawal from the CBSS, as the members of the organisations were no longer considered equal.<5> These instruments include the Crimea Platform, the institution of ‘unfriendly states’, the Baltic expansion of NATO in 2023, the Ramstein Group, which brings together over 50 states providing military aid to the Kiev regime, among others.

The destruction of both Nord Stream pipelines with Germany’s tacit approval can also be placed in the above category. The collective West has erected a new iron curtain, thicker and less permeable than the one during the Versailles and Potsdam eras. The political significance of the Baltic region for Russia has sharply declined, bolstered by the country’s rapid ‘turn to the East’. Russia’s newly adopted Foreign Policy Concept of 2023 does not mention the Baltic region, with greater more attention given to Latin America and Africa.

The natural consequence of the disintegrative processes occurring within the previously flourishing Baltic region of cooperation and fuelled by global geopolitical shifts is the emergence of a new regional geopolitical entity. This new formation is rooted in confrontational geopolitical relations between two opposing geopolitical and geo-economic development paradigms: the Baltic Euro-Atlantic model represented by the Baltic States, which are EU and NATO members, and Ukraine, with the primary political coordinator, the US, being a non-regional actor, on the one hand, and the Baltic Eurasian model represented by Baltic Russia and Belarus — members of the CIS, the Union State, the CSTO and the EAEU, on the other [30].

What place does this new changing Baltic regional geopolitical entity hold in the Eurasian geopolitical reality amidst the collapse of previously dominant ethnic, national and integrative geopolitical processes and systems, and the establishment of a multipolar global geopolitical system with a focus on civilizational geopolitical processes?

Let us try to answer this question by creating a hierarchy of contemporary conflicting geopolitical regional entities in Eurasia. If we consider the Eurasian arc of instability, which stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean and may include the perimeter of the post-Soviet space, depending on the interpretation, as a multi-focal geopolitical macro-region of conflicting geopolitical relations, then we can identify two major de factor geopolitical subsystems within it. These civilizational geopolitical regions are the Euro-Atlantic area (the space of NATO, EU, and other Euro-structures of the Western civilization) and the Eurasian area (Russia and fellow member states of integration associations representing the ‘non-Western’ civilizations of the post-Soviet space. Within these spaces, there are numerous conflicting geopolitical regions linked by various types of conflict relations between two or more state actors forming alliances and other structures [14]. From this perspective, the Baltic States and some neighbouring countries located at the Baltic interface between the Euro-Atlantic and Eurasian regions, such as Belarus and Ukraine, can be considered as a de facto confrontational Baltic geopolitical region of a bipolar type with a complex, mosaic geopolitical structure of conflict relations. These ‘fault lines’ run between states, countries and international organisations. The identified avenues of geopolitical development followed by countries of the Baltic region make it possible to distinguish two subregions in the area: the Baltic-Euro-Atlantic subregion and the Baltic-Eurasian subregion, which are linked by confrontational geopolitical relations.

Conclusions

This study examined several interconnected issues crucial to understanding the substantive and geographical characteristics of the Baltic region. To achieve this, an activity-geospatial geo-spatial approach was utilised in exploring geopolitical processes and systems from the perspective of political geography and geopolitics. Further, a typology of transboundary and transnational regions was proposed and applied to the study of the Baltic region. At the current stage, the most relevant typology is the one with a focus on the quality of regional relationships or their complementarity (regions of cooperation or conflict).

The Circum-Baltic space was examined in the context of Baltic region delineation. It was concluded that from a geopolitical standpoint, different delimitation variants do not contradict each other, representing different facets of a single regional geopolitical system. Therefore, the four ‘geopolitical contours’, defined using different methodological principles, should be considered collectively.

The specifics of geopolitical regionalisation within the Baltic regional geopolitical system were examined across historical periods to elucidate the dynamics of the global geopolitical system. Five geopolitical periods and geopolitical processes of the last two decades were explored to this end. The historical transformation of geopolitical processes, systems and structures in the Baltic region was investigated: from an ethnic and religious-driven geopolitical entity of the Westphalian era, through the imperial-geopolitical phenomenon of the Vienna period to the foundational geopolitical structure of the Versailles and Potsdam eras. It was concluded that the region had a stable bipolar structure from the 18th to 20th centuries, as two centripetal-peripheral geopolitical subregions formed with Prussia (Germany) and Russia (USSR) at its poles.

During the Belovezha era, the dominance of foundational and ethnic-driven geopolitical processes manifested in the collapse of the socialist system and its structures, the dissolution of the USSR, the formation of ethnocentric post-socialist states and their westernization launched integration for the first time in the history of the region. This way, a de facto regional cooperative geopolitical unity — the Baltic geopolitical region — a region with stable geopolitical relations of cooperation. However, after 2014, the escalation of confrontational civilizational geopolitical processes between the countries of the region caused a new iron to fall. The modern bipolar geopolitical entity — the de facto confrontational Baltic geopolitical region, whose members follow different avenues of geopolitical avenues — divided the region into two geopolitical subregions: the Baltic-Euro-Atlantic and Baltic-Eurasian areas.