The adaptation of Russian regions’ economies to the rupture of relations with Europe: the case of Baltic Sea ports

- DOI

- 10.5922/2079-8555-2023-4-4

- Pages

- 62-78

Abstract

Despite the sweeping economic sanctions imposed by Western countries, Russia has managed to avoid a significant recession, experiencing recovery growth. The situation in the regions earlier involved in cooperation with Europe was more complicated. Yet, these territories have also succeeded in reviving their economies and returning to growth. A number of growth areas have emerged in the Russian regions, which continue to develop under sanctions. A prime example of this is Russian seaports. This article examines the factors that enabled Russian businesses, including those operating in Baltic Sea ports, to adapt to the sanctions and continue operations. To do so, a comprehensive analysis was conducted, with a focus on macroeconomic, sectoral, regional, and corporate statistics. In addition, scholarly articles and information from business media were examined, and a survey was conducted among Russian enterprises operating across various industries and regions of the country. This study traces the history of economic relations between Russia and Europe over the past twenty-five years, examining the impact of Western sanctions on Russia’s spatial development, the response of Russian maritime transport to these sanctions, and the adaptation measures taken. It also evaluates the performance of Russian Baltic ports between 2022 and 2023, assessing the long-term risks and threats to their development and exploring the potential for maritime transport growth in the Baltic region under the current circumstances.

Reference

Cooperation with Europe as the main priority of Russia’s post-Soviet foreign economic policy. During the 25—30 years preceding the current geopolitical crisis, the European direction was the main priority of Russian foreign economic and foreign trade policy [1], [2].

The majority of Russian exports went to European countries. In the period from 2011 to 2014, the share of 37 European countries in the total Russian commodity exports was 53—55 %. After the launch of the first wave of anti-Russian sanctions, this share decreased, but not very much — from 2015 to 2021 it ranged from 42 to 49 %. For certain types of goods, it was even higher. For example, in 2021, Europe’s share in Russian gas exports was 79 %, petroleum products exports — 56 %, and oil exports — 48 %.

The situation was similar to the import of goods: from 2011 to 2014, 37 European countries supplied 43—44 % of Russia’s merchandise imports, and in the period from 2015 to 2021 their share was 35—40 % [3].

In addition, in these years, Russia placed its bets on the large-scale attraction of direct and portfolio investments, as well as high technologies from European countries, hoping to modernize its national economy with their help. Foreign investors, mainly European, received significant preferences and benefits that helped them to take good positions in Russian markets. As a result, companies from European countries have opened a large number of their own and joint ventures in Russia to produce various goods and services [4]. For example, in 2014, over 6 thousand German companies operated in Russia with an accumulated investment volume of 22.3 billion euros.<1>

During these years, Russian companies often opened their subsidiaries in European countries, trying to integrate into international value chains. For instance, the NLMK Group still owns three metallurgical enterprises in France and one in Denmark, supplying its products produced in Russia for further processing.<2>

Problem points of Russian-European economic cooperation. It should be noted that Russia has been striving for open and equal economic cooperation with Europe for many years. The European vector of the development of Russia’s foreign economic relations was justified by the confidence of many domestic politicians that cooperation with partners from the EU and other countries, in general, would be long-term, stable and mutually beneficial. This policy remained consistent, despite the fact that many European partners, long before the aggravation of the geopolitical situation in 2014, refused to take into account Russia’s economic interests and applied discriminatory measures towards our country [5], [6], [7], [8].

In particular, in 2006, the Russian Severstal Group received a refusal to purchase the Luxembourg metallurgical company Arcelor. According to many observers, one of the reasons for the refusal was the reluctance of European governments to sell one of the largest producers of ferrous metals in the world to a Russian buyer.<3> A similar story occurred in 2009, when a deal to acquire the German automobile company Opel by Russian buyers fell through. After the deal failed, there were many media reports saying that the reasons for the refusal were politically motivated.<4> General Motors, which controlled Opel at that time, under pressure from the American authorities, did not want to provide Russia with access to Opel technologies and patents, even though these technologies were mass-produced and could hardly be considered the most advanced and sensitive from the point of view of military rivalry.<5>

It is also necessary to recall that Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, which border Russia, have for many years shown themselves to be disloyal and unreliable transit countries for freight flows from and to Russia. These countries often introduced restrictions for Russian exporters and importers, inflated prices for the transportation of goods across their territory, created obstacles to the construction of transit transport infrastructure, and put forward various political demands. In particular, in 2013, Poland refused to approve the project for the construction of the Yamal — Western Europe-2 gas pipeline, demanding as an ultimatum that in the section leading to the Polish border, the pipe should not pass through the shorter and more reliable route through Belarus, but through Ukraine.<6> This story became one of the main reasons that forced the Russian company Gazprom to switch to the implementation of the Nord Stream project, within the framework of which gas went directly to Germany, bypassing the unfriendly countries of Eastern Europe.

Development of Russian ports in the Baltic. Until very recently, Russia continuously advanced its infrastructure to bolster and facilitate economic and trade ties with Europe across various domains. This policy was accompanied by the construction of new ports, berths, terminals, railway approaches, and specialized warehouse areas on the western borders of Russia. At the same time, housing for workers and other infrastructure for port, customs, phytosanitary and other services were built in the port areas. Particular emphasis was placed on the augmentation of cargo traffic through the Baltic Sea, given that this route served as the shortest and most convenient pathway to Russia’s primary trading partners in Europe, including Germany, France, the Netherlands, and others [9], [10], [11]. As a result, transport operations in the Baltic, both freight and passenger, developed very quickly. In the mid-1990s, transport departments and businesses managed to convince the then Russian president to sign decrees on the construction of three new ports in the Leningrad region — Ust-Luga, Primorsk and Batareynaya Bay. This decision fundamentally changed the situation with the Baltic transit in favour of Russia, although the leadership and business of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania resisted this development in every possible way, trying to maintain their pricing and political influence on Russian-European trade relations. The construction of new large ports in the Gulf of Finland can be considered one of the main successes of Russian spatial policy in recent decades. This success made it possible to largely get rid of the dictates of the disloyal transit countries of Eastern Europe and gave a serious impetus to the economic development of almost all regions of North-West Russia.

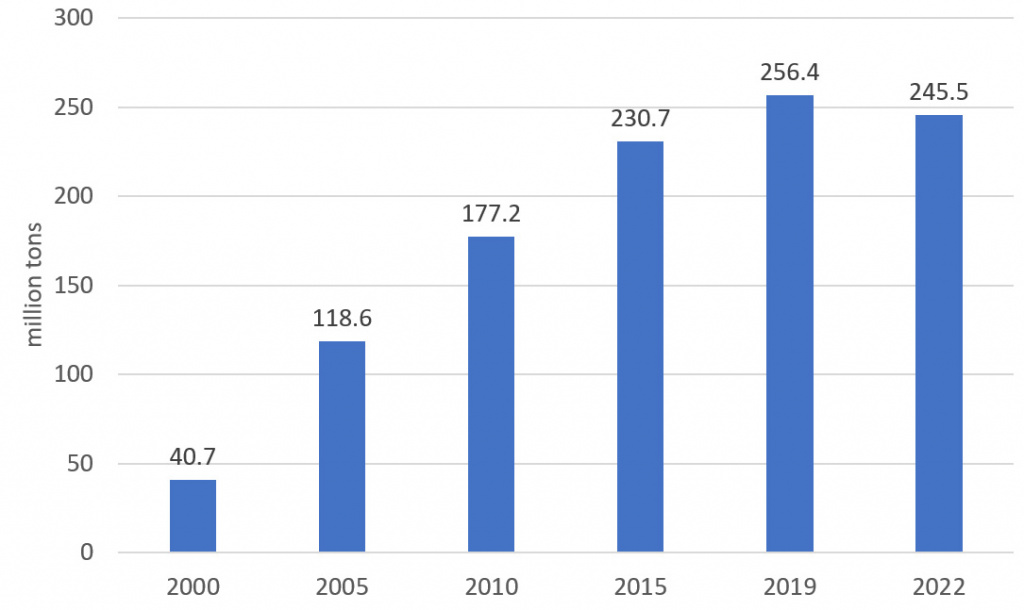

The expansion of Russian port facilities in the Baltic Sea was executed with deliberate intent and systematic precision, ensuring a sustained and consistent growth in maritime cargo turnover (Fig.).

|

| 1 |

| Dynamics of growth in cargo turnover of Russian ports in the Baltic, million tons/year |

|

Source: compiled by the authors based on data: Transport of Russia, Information and Statistical Bulletin 2022, 2023, Ministry of Transport of the Russian Federation, URL: https://mintrans.gov.ru/ministry/results/180/documents (accessed 08.08.2023) ; Russian Baltic ports. “Window to Europe at the beginning of the 21st century”, Morstroytekhnologiya, URL: https://morproekt.ru/articles/science-artiles/obzornye-stati/1204-russian-baltic-ports (accessed 08.08.2023) ; All cargoes of Russia, Seaports, 2011, № 1, p. 79— 86. All cargoes of Russia, Seaports, 2016, № 1, p. 71. All cargoes of Russia, Seaports, 2020, № 1, p. 65. All cargoes of Russia (in Russ.), Seaports, 2023, № 1, p. 57. |

Thus, domestic ports in the Baltic Sea increased their cargo turnover by 6.3 times in the period from 2000 to 2019. This allowed Russian ports to take the first three places in the port hierarchy of the Baltic Sea in 2019—2020 (Table).

|

Port |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Ust-Luga |

103.852 |

102.602 |

109.377 |

|

Saint Petersburg |

59.879 |

59.884 |

62.031 |

|

Primorsk |

61.024 |

49.302 |

52.998 |

|

Gdańsk |

52.154 |

49.038 |

53.213 |

|

Klaipeda |

46.26 |

47.79 |

45.619 |

|

Gothenburg |

38.9 |

37.9 |

36.9 |

|

Swinoujscie |

32.175 |

31.178 |

36.9 |

|

Rostock |

25.7 |

25.1 |

28.68 |

|

Gdynia |

23.957 |

24.662 |

26.686 |

|

Tallinn |

19.931 |

21.327 |

22.397 |

|

Total |

463.832 |

447.782 |

471.121 |

|

Source: Report Cargo Throughput in Top 10 Baltic Ports In 2021 Rebound After Tough 2020. February 2022, Port Monitor, p. 3, URL: www.actiaforum.pl (accessed 08.08.2023). |

|||

As can be seen from the table, in 2021, the three leading Russian ports accounted for almost half of the cargo turnover of the Baltic top ten. Let us note another important result of the changes that took place during that period: now almost the entire market for the transportation of Russian oil and petroleum products in the Baltic is controlled by two domestic ports — Primorsky and Ust-Luga.

Adaptation of the Russian economy to Western sanctions. After the start of a special military operation in February 2022, Western countries, primarily European ones, introduced numerous anti-Russian bans. For example, leading foreign sea container carriers went out of business with Russia. European ports introduced a ban on the entry of ships carrying the Russian flag, as well as the loading of ships, regardless of their flag, destined for Russian ports. The restrictions extended to the transit of Russian cargo through European ports, bunkering services for all vessels owned by Russian shipowners, and the entry of automobile rolling stock (both freight and passenger cars) displaying Russian license plates. In addition, the transshipment of containers with Russian cargo by rail at border crossings was limited. Ships flying the flags of EU countries were prohibited from entering Russian ports, a closed skies regime was introduced for the Russian air fleet, etc. EU countries have essentially abandoned imports from the Baltic ports of both large cargo consignments (oil cargo, coal, fertilizers, timber, etc.) and goods exported in small consignments.

Many experts, both in the West and within Russia, anticipated that the implementation of extensive sanctions would deliver a significant blow to the Russian economy, potentially causing a substantial setback. As subsequent events showed, the blow was indeed strong [12], [13]. However, the speed of adaptation of the Russian economy to external pressure turned out to be very high, which made it possible to significantly mitigate the consequences of sanctions and to quickly commence economic restructuring.

For instance, as surveys conducted by the Institute of National Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences showed, in the spring of 2022, many Russian enterprises began searching for alternative suppliers of sanctioned products. 36 % of surveyed enterprises responded that they were looking for alternative suppliers of sanctioned products abroad, and 70 % of surveyed enterprises — within Russia. In addition, in the spring of 2022, 31 % of enterprises began searching for new markets; 21 % launched the production of new types of products, and 15 % began to rebuild production (through modernization, repairs, etc.).

In 2023, Russian enterprises not only sustained their commitment to adaptation but also heightened their efforts, with a discernible increase in the frequency of employing active adaptation methods. In particular, in the spring of 2023, the share of enterprises that began modernizing their manufacturing process increased to 33 %. As a result, in the spring of 2023, 32 % of Russian enterprises came to the conclusion that they were generally not affected by the sanctions (in the spring of 2022 there were only 19 % of such enterprises)<7> [14].

Intensive efforts to adapt to the sanctions were also undertaken at various levels, including Russian federal ministries and departments, regional administrations, and major state-owned companies. According to the Ministry of Economic Development (MED) of the Russian Federation, 309 measures were launched in Russia to provide anti-sanctions support to the national economy in 2022. In particular, the loan debt of large businesses was restructured in the amount of 5.9 trillion roubles, which allowed domestic companies to save 36.6 billion roubles on interest payments. The so-called parallel import of products (without the consent of copyright holders through informal channels), the suppliers of which officially refused to import them into Russia, was also legally permitted. At the same time, the Government of the Russian Federation introduced a moratorium on unscheduled business inspections for 100 types of federal, 33 types of regional and 7 types of municipal control procedures.

In addition, numerous measures have been taken to support certain sectors of the Russian economy.<8> For example:

— until July 30, 2027, the value added tax (VAT) on hotel accommodation services was zeroed out;

— a zero profit tax was established for national IT enterprises for 2022—2024 (which, according to estimates by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation, will provide the industry with annual cost savings of 3.7 billion roubles);

— in 2022 enterprises of the Russian agro-industrial complex received over 150 billion roubles in preferential loans at a rate not exceeding 5 % per annum;

— over 122 billion roubles were allocated to domestic air carriers in 2022; it was direct budget support to compensate for losses incurred due to the severance of transport links with Western countries;

— Russian Railways received 250 billion roubles from the National Welfare Fund for additional capitalization; the primary objective of the additional capitalization was to supplement budgetary funding, specifically earmarked for the modernization of railways in the Far East and the procurement of rolling stock from Russian suppliers.

— Numerous measures were implemented to extend anti-crisis support to households, encompassing additional payments to families with children, totalling approximately 440 billion roubles in 2022. The budget allocated funds for public works amounting to 25 billion roubles, engaging unemployed citizens in the process. Additionally, there was an increase in budgetary support for professional retraining initiatives. Remarkably, Russian citizens exhibited responsible behaviour, refraining from consumer panic, mass withdrawal of deposits from banks, or organizing strikes.

Due to the active adaptation activities of the state, businesses and households, the fall in Russia’s GDP at the end of 2022 was not 8—12 %, as many leading foreign and domestic analytical organizations expected at the beginning of events, but only 2.1 %.<9>

The impact of Western sanctions on the development of Russian regions.The restructuring of economic processes caused by geopolitical upheavals in 2022– 2023 greatly influenced the spatial development of Russia [15], [16]. The significant decrease in economic connections with Western countries, particularly those in Europe that imposed sanctions, prompted a discernible reorientation of Russian foreign trade and transport flows [17], [18], [19]. Under the new conditions, transport routes leading to the Far East, the Barents and Caspian Seas, as well as the countries of Central Asia have become of particular importance for Russia. Currently, these areas are experiencing rapid development, evident not only in the escalating trade turnover with nations supportive of Russia but also in the rising investments directed toward projects facilitating the enlargement of foreign trade relations in the southern and eastern regions of Russia. This includes the construction of new ports, the expansion of existing ones, the enhancement of border crossings, the augmentation of transport route capacities, and the relocation of certain types of production activities to the east, among other initiatives.

At the same time, the imposition of sanctions has led to a decline in transport flows directed towards European countries, particularly those traversing the sea and land borders in the western part of Russia. It is very likely that this state of affairs will continue in the medium term. A possible easing of geopolitical tensions in the more distant future will most likely lead to a gradual restoration of economic ties between Russia and Europe, but it is already clear that this restoration will not happen soon and will entail serious changes in the structure of cross-border exchanges [20].

This development of events quite seriously affected the state of affairs in the Russian regions adjacent to the Baltic — St. Petersburg, Leningrad, Kaliningrad, Pskov and Novgorod regions, and the Republic of Karelia. This was primarily expressed in a decrease in the workload of a large number of local enterprises in the transport complex and related industries serving it.

Furthermore, a decline in output occurred at Russian enterprises reliant on raw materials and components from unfriendly countries. This impact was notably felt in the Baltic regions of Russia, where a significant number of such enterprises were located. For instance, at the onset of 2023, in the automotive cluster of St. Petersburg, production at two plants—Nissan and General Motors—was nearly halted, while at the third plant, Hyundai-KIA, only the manufacturing of specific components for cars of these brands continued.<10> The Tikhvin Carriage Works in the Leningrad region was shut down for more than two months in 2022 due to a shortage of cassette bearings of Western origin.<11>

The complete or partial closure of a number of joint ventures due to the departure of some foreign investors also led to negative consequences. In particular, cassette bearings ceased to be produced at the Russian factories of the Swedish company SKF and the American company Timken, which supported the sanctions and left the Russian market.

Many Russian enterprises that previously exported their production to European countries also reduced their output. For example, exports of lumber from Russia at the end of 2022 fell by about 21—22 %, mainly due to the fact that their supplies to European countries were blocked as a result of sanctions.<12> The forest industry of North-West Russia, which was most dependent on the export to Europe, suffered the most.<13>

The development of maritime transport is a success story in overcoming the consequences of anti-Russian sanctions. Contrary to widespread expectations, the Russian maritime transport sector, including companies catering to international transportation, managed to navigate through the challenges and generally avoided a crisis in the years 2022—2023.

Good results were shown both in Russia as a whole and in the Baltic. Despite the introduction of several packages of sanctions against Russian individuals and legal entities, in 2022, Russian ports managed not only to maintain the level of cargo work achieved in the pre-pandemic 2019, but also to exceed it. Domestic transport companies managed to turn the situation around in just three to four months: by July-August 2022, cargo transshipment volumes rebounded, and subsequently, cargo flows between Russia and other countries around the world continued to witness positive growth. At the end of 2022, the total cargo turnover of Russian sea ports increased by 0.7 % compared to 2021 and amounted to 841.5 million tons, including dry cargo — 404.7 million tons (– 2.0 %), for liquid cargo — 436.8 million tons (+ 3.4 %). 667.5 million tons (+ 1.0 %) were shipped for export; imported cargo amounted to 36.3 million tons (– 10.2 %); transit amounted to 60.7 million tons (– 5.9 %); cabotage — 77.0 million tons (+ 10.7 %).

As for the Baltic basin, which was most affected by sanctions, the results for 2022 were as follows: total cargo turnover — 245.5 million tons (– 2.9 %), including dry cargo — 96.9 million tons (– 18.1 %); liquid cargo — 148.6 million tons (+ 10.4 %). The cargo turnover of single ports was: Ust-Luga — 124.1 million tons (+ 13.5 %); Primorsk — 57.1 million tons (+ 7.8 %); Big Port of St. Petersburg — 38.8 million tons (– 37.5 %); Vysotsk — 16.0 million tons (– 5.2 %). It should be noted that the decline in cargo work in St. Petersburg is associated with a sharp decrease in the handling of container cargo, in which the city port has always specialized. In 2022, Russia was no longer served by the world’s leading container companies, and restructuring this area using internal resources requires quite a lot of time.

The positive dynamics of the development of Russian maritime transport continued in 2023. In Russia as a whole, the growth of maritime transport accelerated compared to 2022, and in the Baltic the situation has changed from a decrease in the volume of transport work to recovery growth. In January-July 2023, cargo turnover at Russian seaports increased by 9.3 % compared to the corresponding period in 2022 and amounted to 526.8 million tons, including dry cargo — 263.9 million tons (+ 16.8 %); liquid — 262.9 million tons (+ 2.6 %), including oil — 161.5 million tons (+ 6.4 %); petroleum products — 75.5 million tons (– 5.7 %); liquefied gases — 20.2 million tons (– 4.4 %); food products — 3.4 million tons (+ 38.6 %). Export load amounted to 413.0 million tons (+ 7.8 %); 22.8 million tons (+ 11.1 %) were handled for import, 38.9 million tons (+ 7.1 %) — for transit, 52.1 million tons (+ 24.3 %) — for cabotage.

In the Baltic, the results of the first 7 months of 2023 were as follows: cargo turnover — 149.0 million tons (+ 3.8 %), of which dry cargo — 66.2 million tons (+ 17.5 %), liquid cargo — 82.8 million tons (– 5.1 %). At the same, time the cargo turnover of single ports was as follows: Ust-Luga — 70.2 million tons (+ 1.6 %), Primorsk — 38.6 million tons (+ 9.5 %), Big Port of St. Petersburg — 26.4 million tons (+ 9.3 %), Vysotsk — 7.8 million tons (– 16.3 %).

These indicators highlight the resilience of Russian marketers, logisticians, port workers, railway workers, shipowners, and other market participants utilizing maritime transport. They successfully implemented an effective asymmetric response to the sanctions, nearly fully compensating for the incurred losses. Various methods were employed to counter politically motivated sanctions restrictions, showcasing adaptability and strategic manoeuvring within the industry.

For example, according to Western business media reports, at the beginning of 2023, the shadow tanker fleet serving the Russian export of oil and petroleum products bypassing sanctions amounted to over 600 vessels.<14> Moreover, this fleet was formed in 2022. Simultaneously, shipbuilding, especially that of gas carriers, is gaining momentum within Russia. The surge in the number of such vessels will contribute to circumventing sanctions during the transportation of hydrocarbons.

Activities of Russian Baltic ports to overcome the consequences of sanctions crisis. The ports of the Russian Baltic, due to their orientation towards European countries, suffered from sanctions more than ports of other seas in 2022. However, both the ports themselves and the cargo carriers responded very quickly and flexibly to the situation.

Firstly, the Baltic transport industry made concerted efforts to swiftly redirect delivery routes for traditional cargo. The outcome was a swift reconfiguration of Russian transport capacities, initially centred on the Baltic direction. These capacities were promptly employed not only for connections with Europe but also for the vigorous transportation of goods to other countries. As a result, the Baltic ports began to handle much more cargo destined for Africa, Latin America and Asia.

In particular, the export of gasoil and diesel fuel from Russia to North Africa in the first quarter of 2023 (2.3 million tons) increased by 7.2 times compared to the first quarter of 2022 (0.32 million tons). Two thirds of this export go through the Baltic ports.<15> In addition, supplies of Russian petroleum products to Latin America are also growing rapidly: in January—April 2023 alone, 1.5 million tons were exported in this direction, while for the full year 2022, the volume of supplies amounted to only 0.21 million tons. In this case, as the business media report, a significant share of the supply of petroleum products also goes through the ports of the Gulf of Finland, primarily from Primorsk.<16>

By the end of 2022, there had been an increase in the export of Russian lumber to North Africa, the Near and Middle East (Iran, UAE, Iraq, Jordan, Israel, Tunisia, etc.). Compared to 2021, the increase in lumber exports to this region was 18 %, and the total volume of supplies reached 1.2 million tons.<17> And in this case, the main beneficiaries were the main ports for the export of Russian timber — Ust-Luga and St. Petersburg.

The reorientation of transport flows passing through the Russian Baltic will, apparently, continue. For instance, PhosAgro Group plans to double its fertilizer exports to Africa, taking advantage of the proximity of its new plant in Volkhov to the Russian ports of the Gulf of Finland.<18>

In addition, there has been a notable increase in the export of products from Belarus and other post-Soviet countries through the ports of the Russian Baltic. In particular, in the first half of 2023, the transportation of Belarusian export cargo through Russian ports increased fourfold compared to the first half of 2022 — from 1.5 million tons to 6 million tons.<19> Almost the entire increase in transit from Belarus goes through the ports of St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region. Another example is the transportation of Kazakh coal, the export of which through the ports of the Russian Baltic in August-November 2022 increased by 27 % (to 3.7 million tons) compared to August-November 2021.<20>

Secondly, cargo carriers began to change the types of cargo exported from Russian Baltic ports, which allows them to reload the freed-up capacity. In particular, there have been reports of an increase in the volume of grain exports passing through Baltic ports. In 2023, a significant development took place as one of the terminals at the Vysotsky port in the Gulf of Finland underwent conversion for the purpose of exporting grain, with a capacity of handling up to 4 million tons annually. The Sodrugestvo Group has announced the plan to construct a new grain terminal in the port of Ust-Luga with a declared transshipment capacity of 10 million tons per year.<21> Since the majority of Russian export grain goes to the countries of the Middle East and Africa, European sanctions are generally unable to cause significant harm to the Russian agricultural and transport sector which supply it.

Besides, there has been a significant increase in cabotage transportation in the direction of the Kaliningrad region. Cabotage transportation of containers between Russian regions in the Baltic increased 35 times in 2023.<22> This made it possible not only to overcome barriers introduced by unfriendly countries for land transportation to the Kaliningrad region, but also to support the Kaliningrad port, whose cargo turnover by the end of 2023 should exceed the results of 2022 by 6—7 %.<23>

Thus, the response of Russia’s Baltic ports, as well as transport and manufacturing companies cooperating with them, was not only fast, but also very efficient. It should be noted, however, that the described successes in solving current problems do not in themselves guarantee the elimination of risks and threats of a longer-term nature.

Risks and threats to the long-term development of cargo transportation through the ports of the Russian Baltic. The political background of the sanctions adopted against Russia makes further developments difficult to predict. According to many foreign and Russian analysts, the economic potential of Western sanctions is close to exhaustion.<24> However, as recent events have shown, in attempts to cause damage to Russia, unfriendly countries are ready to resort to direct military pressure and even terrorist acts against foreign trade infrastructure. It was sabotage in the Baltic Sea where the underwater pipelines Nord Stream and Nord Stream 2, intended for transporting Russian gas to Europe, were blown up on September 26, 2022. Official investigations into the terrorist attack, carried out by Denmark, Sweden and Germany, are being conducted extremely slowly and opaquely, which, in fact, leaves no doubt that behind the explosion is a coalition of states unfriendly to Russia, ready for extremely dangerous actions of a military-political nature.

He geography of the Baltic Sea indeed presents a strategic challenge, as ships aiming to access the Atlantic Ocean must navigate through the relatively narrow Danish Straits. This passage, being crucial for maritime traffic, could potentially be subject to control or monitoring by warships of nations that are unfriendly to Russia. In this context, if current economic sanctions prove ineffective, there is a possibility that cargo ships traveling from Russian ports to foreign markets and back may face ‘unscheduled’ inspections and other delays, potentially escalating to a complete blockade of traffic by NATO warships.

Of course, Russia has tools for counter-military-political pressure on unfriendly countries if they try to complicate the movement of foreign trade cargo through the Baltic. However, firstly, an open military-political confrontation can block the activities of almost any maritime transport in the Baltic. Secondly, as the Nord Stream explosion showed, unfriendly countries can successfully shift the blame for hostile actions onto ‘unknown terrorists’ and not provide clear reasons for retaliatory military-political actions.

When planning the development of the Baltic ports, these risks must undoubtedly be taken into account [21], [22], [23]. In this sense, the situation in the Baltic for the Russian maritime transport and port facilities is worse than, for example, in the waters of the Japanese, Barents and Caspian Seas, where organizing a ‘soft’ blockade of the movement of merchant ships by unfriendly countries will be either extremely difficult or impossible.

Indeed, military-political risks are not the sole threat to Russian maritime transport and port facilities in the Baltic. The industry is susceptible to more conventional challenges as well. The dynamics of maritime transport are intricately tied to the overall economic situation, and traditional issues such as economic fluctuations can impact the industry significantly. Possible economic crises, especially large-scale ones, in the global and/or Russian economy could also seriously undermine the dynamics of cargo transportation and port operations.

Prospects for the development of Russian Baltic ports under new conditions. When assessing the opportunities for the development of maritime transport and port facilities on the Baltic Sea, both positive and negative factors should be taken into account.

The competitive advantages of the Baltic ports of Russia include a high level of development of coastal infrastructure and a large share of modern equipment and technologies. Besides, the coast of the Gulf of Finland is reliably connected by numerous transport routes with key Russian regions producing the main export products — oil, petroleum products, timber, metals, chemical products, etc., as well as with Russian regions that consume a significant part of imported raw materials, components, machinery and equipment. Also, the advantages of local ports include the fact that the shortest trade routes from Russia to Western Europe, Central and Latin America, Western and South Africa pass through the Baltic.

Important factors for future development include the high adaptive capabilities of the Russian transport complex in relation to various crisis phenomena, confirmed in 2022—2023, and its ability to quickly find new directions for trade relations. In addition, the Russian authorities plan to continue to provide broad financial and institutional support to both the entire national transport complex and its Baltic divisions. Moreover, as noted above, many domestic large companies also intend to develop their activities in the Baltic direction, primarily with the aim of expanding export supplies.

The relative weaknesses of the transport complex in the Baltic include the crowding of ports on a small section of the coast of the Gulf of Finland and the possibility of traffic jams on shipping routes, especially during winter freezing of coastal waters. Besides, the enclave position of the Kaliningrad region, surrounded by unfriendly countries, in modern conditions significantly complicates the full integration of its transport complex with the rest of the Russian economy.

The above-mentioned risks of a military-political nature may also complicate the development of Russian ports and maritime transport in the Baltic. However, it seems that for now the likelihood of attempts to create permanent obstacles to the movement of Russian merchant ships in the Baltic is not very high, since this will lead to a sharp aggravation of the general situation, which will seriously hit the maritime transport flows of the initiators of such aggression.

Historical experience shows that compliance with economic sanctions almost always weakens over time. Business, including those in the countries that initiated the sanctions, while suffering obvious losses, is much less interested in complying with them than the political authorities. As a result, business structures of countries drawn into political confrontation are gradually finding new ways to bypass sanctions, expanding mutually beneficial trade and economic ties [24], [25], [26]. Therefore, there is little doubt that in the case of anti-Russian sanctions, a similar development of events will be observed.

Thus, the analysis of the situation shows that at this stage, the prospects for the development of Russian maritime transport and port facilities can be assessed as quite positive. It appears that positive development factors generally outweigh existing problems, risks and threats.

Apparently, the Russian Ministry of Transport also believes that positive development factors prevail over negative ones. As a result, the Ministry of Transport of the Russian Federation published the approved passport of the federal project “Development of railway approaches to the seaports of the North-Western Basin” on August 10, 2023. In accordance with this document, by the end of 2024, the carrying capacity of railway approaches to the ports of the North-Western Basin will have been increased to 145.6 million tons, and by the end of 2030 — to 220 million tons.<25> The implementation of these plans will, of course, have the most positive impact on the development of Russian Baltic ports.

Conclusion

1. Anti-Russian sanctions and the partial severance of trade and economic relations with European countries have caused considerable damage to the Russian regions. At the same time, a number of industries from regions adjacent to the Baltic Sea basin suffered more than others, since their economic activities were largely focused on cooperation with European partners.

2. The Russian economy, represented by business, federal and regional government structures and households, managed to quickly and flexibly respond to the sanctions, preventing a serious crisis in the country in 2022 and launching recovery growth in 2023. One of the important elements of adaptation to sanctions was the reversal of Russian spatial development policy to the south and east. At the same time, the activities of Russian maritime transport and port facilities have become a success story within the framework of the anti-sanctions policy.

3. The ports of the Russian Baltic suffered from sanctions more than the ports of other sea basins, because they were focused on trade cooperation with European countries, which in 2022 severed a significant part of economic ties with Russia. However, active efforts to find new trading partners and new cargo allowed these ports to refocus their activities on new directions and significantly soften the blow of the sanction crisis.

4. Despite the existing problems, risks and threats, including those of a military-political nature, Russian maritime transport and ports in the Baltic Sea have generally good prospects for further development, including thanks to the deep modernization of the port sector carried out in recent years. The development of maritime transport, in turn, will provide a significant impetus for economic dynamics in the regions of Northwest Russia.