The impact of the food embargo on consumer preferences and cross-border practices in the Kaliningrad region

- DOI

- 10.5922/2079-8555-2023-2-4

- Pages

- 62-81

Abstract

The Russian food market has been a fascinating subject for researchers investigating food security risks and ways to mitigate them since the embargo was imposed in 2014. The Kaliningrad region, an exclave of Russia, responded more sensitively to the restrictions than any other territory of the country due to the heavy dependence of its food market on imported finished products and raw materials, as well as the transit from Russia via third countries. This study aims to explore how the consumer preferences of Kaliningraders changed in 2014—2021 under the food embargo. The research also investigates changes in the cross-border mobility of the region’s residents with regard to the practice of shopping for groceries in neighbouring countries. The principal method used in the study is survey research. A survey of 1,019 respondents was conducted in September 2021. Additionally, a comparative analysis of average food prices in the region and neighbouring countries from 2012 to 2019 was carried out based on data from Kaliningradstat and the national statistics services in Poland and Lithuania. The ways to obtain embargoed food were systematised using content analysis of social media, advertising and joint purchase services, travel agency websites, regional news portals and blogs. The study found that rising prices for commodity groups falling under the import ban were the most significant change in the regional food market. As a result, the share of Kaliningrad and Belarusian manufacturers in the regional market basket of consumer goods rose dramatically, as the volume and range of products increased and new manufacturers entered the market. At the same time, the dependence of purchases of “sanctioned” goods on non-material reasons (quality, personal preferences) determined Kaliningraders’ continued commitment to the “old” strategies despite significant restrictions.

Reference

Introduction and Problem Statement

Regional food markets are influenced not only by internal (local socio-economic and institutional conditions) but also by external factors. Some of them have a more profound effect on border regions. These include the border regime and its changes, which determine the freedom of movement of people and goods [1], as well as the price policy of sellers on both sides of the border. Cross-border price gradients are important for many market players, as they determine the preferences of residents buying food products, the strategy of foodstuff processors purchasing agricultural raw materials, and the policy of stores and retailers [2], [3].

Russia’s restrictions on the import of agricultural produce and food products from some Western countries introduced in 2014 impacted all food market participants — from producers and processors to trade organizations. These changes affected the consumer whose usual food preferences had to transform. The Kaliningrad region as an import-dependent region in terms of food faced a radical market restructuring. In addition, in the Russian exclave, the problems of economic availability of food intensified. This was both the direct impact of the food embargo and the result of the high sensitivity of the residents’ incomes and the regional economy to the ruble exchange rate [4; 5] and the growing gap between the regional and the Russian average purchasing power for a wide range of products [6].

This paper aims to assess the transformation in consumer preferences in the Kaliningrad region under the influence of the food embargo between 2014 and 2021. It also considers changes in the exclave residents’ typical cross-border practices of grocery shopping in the neighbouring countries.

Previous Studies

One of the apparent effects of the food embargo on the population of Russia was the growth of consumer prices caused by the reduction in imports, low self-sufficiency in many commodities and reduced competition in the domestic market [7], [8]. Household incomes were also decreasing. Thus there was a shift in consumption to less expensive, often low-quality, goods [7].

Another effect felt by the consumers was an increasingly limited choice [9]. Over the years, it extended but transformed profoundly. New and many “old” domestic producers came into the market, the range of products imported from not embargoed countries expanded, and the available range of elite and dietary products changed in terms of price and/or quality. The possible explanations include low investment attractiveness of the food industry, staff shortage, etc. [10].

Berendeeva and Ratnikova have conducted a comparative study of the effects of changes in price and supply (substitution effects) [11]. They found that the trends differed in rural and urban areas. For example, in cities, the market for fruit and vegetables has undergone much more significant changes than in rural areas, where residents have their own gardens [11]. According to the researchers, the transformations in the capital regions also differed from those in other territories of the country, since until 2014 the share of imported products was higher there.

Some studies prove that the food embargo has led to the growth in the production of certain types of goods in Russia. Volchkova and Kuznetsova note a successful import substitution in Russia in three product groups: poultry, pork and tomatoes [12]. Receiving active state support, agricultural producers often continued to be market-oriented, i. e. they increased the production of crops most popular domestically and internationally sometimes to the detriment of other less profitable but still important products [13].

In this context, the Kaliningrad region is a vivid example of a region that, on the one hand, in 2014, was extremely highly dependent on imported food, on the other hand, tended to lag behind the average Russian level of purchasing power for a wide range of food products.

In addition, the Kaliningrad region saw rapid growth in agricultural production after the introduction of the food embargo. This was largely due to active state support for the agri industry [14]. The potential food market capacity, a large share of unused agricultural land, and a relatively developed food industry also favoured a fairly rapid development of the region’s agri industry [15]. The production of vegetables, fruit and berries, milk and milk products, and meat and meat products has increased many-fold. However, the threshold values for self-sufficiency determined by the “Food Security Doctrine of the Russian Federation” have not been achieved in most industries under sanctions (except for meat production). The food industry kept struggling as it was suffering severely from disruptions to cross-border trade in raw materials (import of meat and milk powder) [14].

There is another range of studies related to the topic of this research. They all focus on cross-border practices and their specific kind, shopping trips to a neighbouring country. Cross-border consumer mobility is associated not only with price gradients but also with the openness of borders [16]. The literature also describes a distinct phenomenon of “shopping for entertainment”. This is trips to another country to buy food products to try something new and unusual [16].

There are three approaches to studying cross-border shopping practices:

1) assessment of the influence of macrofactors stimulating mobility. These include personal income level, differences in currencies and exchange rates, etc.;

2) assessment of meso- and microfactors characterizing the availability of retail facilities and their technical and economic parameters;

3) assessment of personal factors determining consumer behaviour (mobility, taste preferences, the importance of shopping choice, etc.) [17], [18].

Zotova et al. provided a comprehensive summary of the extensive empirical evidence regarding cross-border mobility along various regions of the Russian borders [19]. According to their study, people in the Kaliningrad region had a strong motivation to overcome all the obstacles. The abolition of the local border traffic (LBT) regime did not cause radical changes in consumer behaviour here when it came to shopping in Polish border supermarkets [19]. Our previous studies also prove that residents of the Kaliningrad region, accustomed to travelling abroad to buy groceries, in general, continued doing so after 2014. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic left the exclave’s population almost no choice but to switch to locally available analogues [6].

However, the issue of changing cross-border practices under the influence of external factors that transform the domestic market in regions remains understudied. In addition, it is not only the studies describing the transformation of the level of income and consumption that are interesting but also those highlighting the changes in consumer behaviour caused by the food embargo.

Materials and methods

The study consisted of several blocks. The first was a comparative retrospective analysis of consumer price indices for food products in the Kaliningrad region and in the neighbouring countries of Poland and Lithuania<1> before the imposition of sanctions and counter-sanctions (2012—2013) and between 2014 and 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began, with its impact overlapping the consequences of 2014 restrictions. The aim was to identify the changes in price gradients encouraging cross-border food shopping trips and shopping for products brought from the neighbouring countries. There were several food products selected for the analysis. They all are compatible across Russian (national and regional), Polish and Lithuanian statistics (Table 1). Sources of information were portals of official state statistics services of Russia,<2> Poland<3> and Lithuania,<4> as well as official statistical publications (Lithuania in figures). The cost of goods in Polish zloty and euro was converted into Russian rubles according to “Calculator. Reference portal”.<5> The study used the end of the year data.

|

Name, unit |

||

|

in Russian statistics |

in Polish statistics |

in Lithuanian statistics |

|

Milk and milk products (milk, yoghurt, etc.) |

||

|

Sterilized whole drinking milk, 2.5—3.2 % fat, l |

Sterilized cow’s milk, 3—3.5 % fat, l |

Pasteurized milk 2.5 % fat, l |

|

Full-fat cottage cheese, kg |

Semi-fat cottage cheese, kg |

Cottage cheese 9 % fat, 200 g |

|

Cheese |

||

|

Hard and soft rennet cheeses, kg |

Maturing cheese, kg |

Fermented cheese, 45—50 %, kg |

|

Fresh meat |

||

|

Beef on the bone, kg |

Beef on the bone (roast beef), kg |

Beef ham on the bone, kg |

|

Pork on the bone, kg |

Bone-in pork (loin), kg |

Bone-in pork shoulder, kg |

|

Chickens, chilled and frozen, kg |

Eviscerated chicken, kg |

Broiler chickens, kg |

|

Sausage and cooked meat products |

||

|

Semi-smoked and cooked-smoked sausages, kg |

Smoked sausage products, kg |

Cold smoked sausage products of the highest quality, kg |

|

Fish and Seafood |

||

|

Salted herring, kg |

Salted headless herring, kg |

Salted herring, kg |

|

Vegetables |

||

|

Potatoes, kg |

Potatoes, kg |

Potatoes, kg |

|

Carrots, kg |

Carrots, kg |

Carrots, kg |

|

Bulb onions, kg |

Onions, kg |

Onions, kg |

|

Fruit and berries |

||

|

Apples, kg |

Apples, kg |

Apples, kg |

The second block was an overview of the possibilities for buying goods prohibited for import into Russia after 2014. This involved a content analysis of social networks (VKontakte, Facebook*, Instagram*<6>), ad services (Avito), joint procurement services, travel agency websites, regional news portals (Newkaliningrad.ru, klops.ru, kgd.ru), blogs’ entries on purchasing “sanctioned” products in the Kaliningrad region. The study was conducted in September-November 2022 and included pages of users of social networks and ads that were active at that time. The units of meaning of the studied content were current and archival data on food shopping tours to Poland and Lithuania, information about food delivery services from Poland and Lithuania, and data on trade in “sanctioned” goods in the region. The unit of measure was the number of subscribers in social networks as of November 8, 2022.

The third block involved assessing the changes in consumer preferences for food products and cross-border mobility after 2014 according to a major regional survey conducted in September 2021.

It consisted of 1,019 interviews. The survey used a stratified three-stage quota sampling combined with a random route sampling. The stratification of the territory ensured the representativeness in terms of the spatial differences observed in the Kaliningrad region. Strata were established by factoring in their geographical location, population, economic specialization, and transport infrastructure:

1) regional centre: Kaliningrad;

2) coastal municipalities: Zelenogradsk, Pionersk, Svetlogorsk, Yantarniy and Baltiysk districts;

3) municipalities oriented to Kaliningrad: Guryevsk and Svetlyi districts;

4) municipalities in the centre of the region: Gvardeisk, Chernyakhovsk, Gusev and Polessk districts;

5) municipalities bordering Lithuania: Neman, Nesterov, Krasnoznamensk, Slavsk and Sovietsk districts;

6) municipalities bordering Poland: Ozersk, Pravdinsk, Bagrationovsk, Mamonovo and Ladushkin districts.

The first sampling stage was determining the number of respondents in each stratum by their share in the statistical population. The second stage was finalizing the survey sites factoring in the size of the urban and rural population in each stratum. The third stage was establishing sex and age quotas for respondents in each survey site according to the proportion of sex and age groups in the general population, i. e. the adult population of the Kaliningrad region.

The questions concerned cross-border practices, the role of imported food in the consumption structure, changes in individual food niches and the public perception of them.

Research Results and Discussion

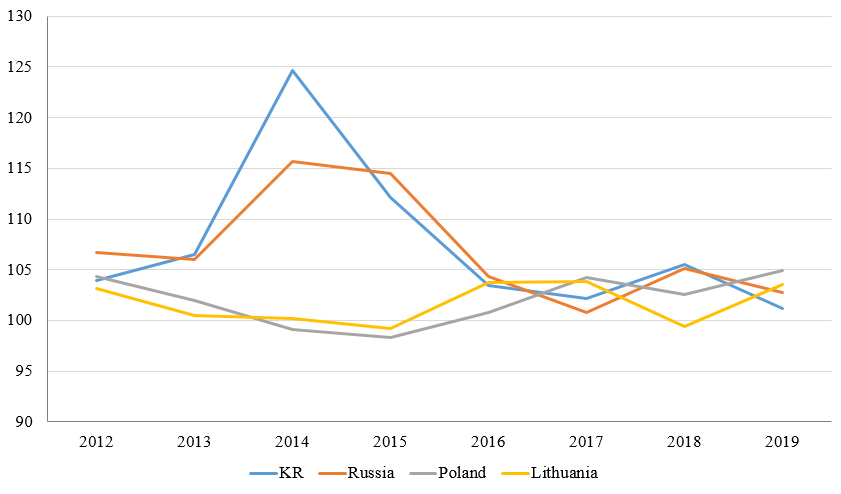

Cross-border price gradients. The changes in the consumer price index for food products in the Kaliningrad region differed significantly from those in the neighbouring countries during almost the entire studied period (Fig. 1). While in the EU countries, the years 2013—2015 were associated with almost zero food inflation, in Russia prices soared by more than 15 %, in the Kaliningrad region by almost 25 %. This was the result of, firstly, the rise in prices for imported goods due to the ruble’s fall against world currencies in 2014 and, secondly, the introduction of the embargo on a range of food products. Starting from 2016, the rate of changes in prices has generally levelled off and fluctuated within 100—105 % of the previous year’s values.

|

| 1 |

| Consumer price index for food products (not including alcoholic beverages and tobacco), % of the previous year |

|

Source: Consumer price indices for goods and services, 2022, EMISS, URL: https://fedstat.ru/indicator/31074 (accessed 10.10.2022) ; CPI-based consumer price changes, 2022, Statistics Lithuania, URL: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?hash=94c9a88f-ec80-4992-9789-7167cc3d9b5a (accessed 10.10.2022) ; Yearly price indices of consumer goods and services from 1950, 2022, Statistics Poland, URL: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/prices-trade/price-indices/price-indices-of-consumer-goods-and-services/yearly-price-indices-of-consumer-goods-and-services-from-1950/ (accessed 10.10.2022). |

As Table 2 shows, the price for considered food products in the region during this period was higher than that for both Polish and Lithuanian goods. In 2012—2013, the largest gap in the prices was recorded for some milk products (1.4—1.5-fold difference), chicken (with Poland, 1.5—1.6-fold), sausage and cooked meat products (2-fold), carrots (with Poland, 1.6 times), potatoes (1.4-fold), apples (1.6-fold). Only fish and seafood were cheaper in the Kaliningrad region than in the neighbouring countries.

|

Product |

Country |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

Milk and milk products (milk, yoghurt, etc.) |

|||||||||

|

Sterilized whole drinking milk, 2.5—3.2 % fat, l |

PL |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

|

LT |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

|

|

Full-fat cottage cheese, kg |

PL |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

LT |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

|

|

Cheese |

|||||||||

|

Hard and soft rennet cheeses, kg |

PL |

— |

— |

1.5 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

LT |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

|

Fresh meat |

|||||||||

|

Beef on the bone, kg |

PL |

1.01 |

0.95 |

0.96 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

|

LT |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|

|

Pork on the bone, kg |

PL |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

— |

— |

— |

|

LT |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

|

|

Chickens, chilled and frozen, kg |

PL |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

|

LT |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

|

Sausage and cooked meat products |

|||||||||

|

Semi-smoked and cooked-smoked sausages, kg |

PL |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.3 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

|

LT |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

|

|

Fish and Seafood |

|||||||||

|

Salted herring, kg |

PL |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

— |

|

LT |

— |

— |

— |

— |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

|

|

Vegetables |

|||||||||

|

Potatoes, kg |

PL |

1.3 |

1.5 |

3.2 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

|

LT |

1.3 |

1.6 |

2.03 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

|

|

Carrots, kg |

PL |

1.6 |

1.7 |

2.4 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

|

LT |

1.1 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.1 |

|

|

Bulb onions, kg |

PL |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

|

LT |

— |

— |

— |

— |

1.1 |

1.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

|

|

Fruit and berries |

|||||||||

|

Apples, kg |

PL |

— |

1.7 |

3.4 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

1.2 |

|

LT |

1.4 |

1.6 |

2.5 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

|

Note: PL — Poland, LT — Lithuania, following the Russian classification of countries of the world.

In 2014, the price differences were the most profound: the prices for fruit and vegetables, and sausages in the Kaliningrad region exceeded those in Poland and Lithuania 2—3.5-fold. However, the fall of the ruble against world currencies in 2014 led to prices soaring for both food products purchased within the region and goods purchased in Poland or Lithuania. Since 2015, buying food abroad has become less attractive, as the price differences have decreased for some of the products considered. At the same time, until 2019, the prices in the region were much higher than those in Poland for milk (1.5-fold), sausage and cooked meat products (1.4-fold), cheeses (1.3-fold), apples (1.2-fold), full-fat cottage cheese (1.2-fold) and than those in Lithuania for milk (1.3-fold) and apples (1.2-fold).

Besides price gradients, throughout the period, Polish and Lithuanian food products differed from those in the Kaliningrad region by their greater variety. This applies primarily to milk and milk products, sausage and cooked meat products, canned meat, vegetables and fruit.

Ways to purchase “sanctioned” goods in the Kaliningrad region. Before the 2020—2021 COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, residents of the Kaliningrad region had numerous opportunities to buy food products in neighbouring countries (Table 3). The regional tourist market offered a wide range of tours to Poland and Lithuania, including stops at supermarkets. However, after 2015, only tours to Poland remained popular, as trips to Lithuania became less profitable due to a significant price increase following its accession to the eurozone. Specialized shopping tours to Polish cities like Gdansk, Bartoszyce, Branjowo, Elblag, and others were particularly popular. In Lithuania, Kaunas, Vilnius, and Klaipeda were the most popular cities for shopping. Transfers and ride-sharing services were also commonly used for these shopping trips. It is challenging to assess the retrospective popularity of such tours. As of November 2022, the share of subscribers in social network groups offering these tours did not exceed 0.6 % of the region’s population.

|

Method |

Description |

Example |

Reach (number of social |

|

As part of tourist trips |

Special shopping tour. Poland: to nearby towns and cities within the LBT area (for example, Gdansk, Branjovo, Elblag, Gdynia, Bartoszyce, Olsztyn). Lithuania: Kaunas, Vilnius, Klaipeda, Trakai. Usually lasts 1—2 days, with a visit to grocery stores: “Auchan”, Lidl, “Biedronka”in Poland, “Maxima”, “Rimi”, “Hypermarket”in Lithuania |

“Tropikanka” (travel agency) |

1,650 (Instagram) |

|

“Tsentr poezdok v Polshu. Transfer” (Eng. Centre for trips to Poland. Transfer) (VK group) |

3,164 (VK) |

||

|

“Baltic-tourist” (travel agency) |

3,008 (Instagram), 1,023 (VK) |

||

|

“Eurotour” (travel agency) |

5,600 (VK) |

||

|

“Perevozoff39” (VK group) |

4,081 (VK) |

||

|

“Shengenskie vizy v Kaliningrade, Polsha, Germania” (Eng. “Schengen visas in Kaliningrad, Poland, Germany”) (VK group) |

2,593 (VK) |

||

|

“Visa-market” (travel agency) |

11,794 (VK) |

||

|

“Kaleidoskop Tour” (travel agency) |

976 (VK) |

||

|

“Golden Travel Kaliningrad” |

1,650 (VK) |

||

|

“Bestway-Kaliningrad. Poezdki v Polshu i Yevropu” (Eng. “Bestway-Kaliningrad. Trips to Poland and Europe”) (VK group) |

1,332 (VK) |

||

|

“Shop-tury v Polshu, transfer, dostavka tovarov” (Eng. “Shop-Tours to Poland, transfer, delivery”) (vipbus39, VK group) |

3,433 (VK) |

||

|

Sightseeing tours of the cities of Poland and Lithuania including a visit to a shopping centre |

Most travel agencies of the Kaliningrad region |

— |

|

|

Ride-sharing. Transfers (individual and group) |

“Kaliningrad. Poputchiki. Poezdki v Polshu” (Eng. “Kaliningrad. Fellow Travellers. Trips to Poland”) (VK group) |

4,087 (VK) |

|

|

IE Berezhnoy A. N. (ride-sharing type of trips) |

2,178 (VK) |

||

|

Food delivery from Poland and Lithuania |

The service is provided by companies that specialize in organizing the delivery of both food and non-food products. There are also courier services or parcel delivery from Poland and Lithuania from other countries to Kaliningrad. In addition, they provide delivery of goods to Russia. Group buying. |

“Shop-tury v Polshu, transfer, dostavka tovarov” (Eng. “Shop-Tours to Poland, transfer, delivery”) (vipbus39, VK group) |

3,433 (VK) |

|

“Tovary iz Polshi. Kaliningrad” (Eng. “Goods from Poland. Kaliningrad” (VK group) |

8,050 (VK) |

||

|

BR39.RU (online store, LLC “S22”) |

10,359 (VK) |

||

|

Allegroexpress.ru (online store) |

2,801 (VK) |

||

|

FastBox.ru (online store) |

20,073 (VK) |

||

|

Allegro39.ru (online store) |

15,680 (VK) |

||

|

“Polskie produkty. Polska_39” (Eng. “Polish products. Polska_39”) |

464 (“VK”), 8,448 (“Instagram”) |

||

|

“Polskie produkty s dostavkoi” (Eng. “Polish products delivery”) |

1,320 (Instagram) |

||

|

“Sovnestnye pokupki v Kaliningrade SP39.RU” (Eng. “Joint purchases in Kaliningrad SP39.RU”) (Internet portal) |

Views of food purchasing in Poland: from 500 to 2,000 (“VK”) |

||

|

Purchases at retail outlets in Kaliningrad and the region |

Retail outlets in the Kaliningrad region, including markets, small shops, trade stands, unregulated street trading — pop-up stalls, and car boot selling (including with truckers as intermediaries). City fairs |

Independent stores and outlets in shopping centres, mini-markets |

— |

Note: *In three days, customs officers seize more than 100 kg of sanctioned products in Kaliningrad stores, 2022, KGD.RU, URL: https://kgd.ru/news/society/item/98651-za-tri-dnya-tamozhenniki-izyali-bolshe-100-kg-sankcionki-v-m... (accessed 08.11.2022) ; Raid in Kaliningrad to curb illegal trade, 2022, Rambler, ULR: https://finance.rambler.ru/other/42668864/?utm_content=finance_media&utm_medium=read_more&am... (accessed 08.11.2022).

The introduction of a simplified LBT regime between Russia and Poland in 2012 stimulated bilateral cross-border passenger flows and, thus, the development of retail and wholesale trade in Polish voivodeships along the state border with the Russian Federation [20], [21], [22], [23]. Some Polish shops offered free shopping tours to attract buyers from the Kaliningrad region. Free bus trips to the Avangard shopping centre in Bartoszyce (59 km from Kaliningrad) in 2016—2018 are an illustrative example of this. Existing until 2016, the LBT regime undoubtedly contributed to the increase in the consumption of food products purchased in Poland by the residents of the exclave. The suspension of the regime reduced cross-border cooperation and similar cross-border practices, although it did not stop them [24], [25], [26].

The international political situation and relations with neighbouring countries encouraged the development of cross-border business, which in many cases was selling goods from Poland and Lithuania on the Kaliningrad market. This includes delivering products from neighbouring countries and selling them in the region.

A review of food delivery services from Poland and Lithuania shows that their providers are mostly organizations engaged in the delivery of goods (including non-food products) from Europe via specialized online stores. Subsequent delivery to other regions of Russia has increased their popularity among their residents. Therefore, the coverage of such social networking groups is several times (from two to five) higher than that of groups organizing shopping tours. At the same time, users from other regions of Russia are more likely to order non-food products than food products. According to the current data, food delivery services are few and far between, reaching up to 1 % of the region’s population.

The range of products from Poland and Lithuania in the region’s retail trade includes mostly milk and milk products, cheeses, meat and sausage and confectionery products. The retail outlets for these goods were diverse: food markets, shops and trade stands, and unregulated street trading (pop-up stalls, car boot selling). In the regional news portals, the latest information on the destruction of seized “sanctioned” food dates back to September 2021. At the same time, according to the Kaliningrad customs, they seized more than a ton of “sanctioned” food only in 2021.<7>

It is important to note that the result of the increased difficulty of purchasing”sanctioned” goods in the neighbouring countries is not only their gradual replacement by their counterparts produced in other regions of Russia and countries not subjected to the food embargo but also the emergence of new industries in the region. For instance, “Pan Boczek” in Kaliningrad produces national Polish meat delicacies; local artisan manufacturers make “sanctioned” kinds of cheese in the towns of Neman (“Tilsit-Ragnit”), Guryevsk (“Shaaken Dorf”), Gusev (“Branden”), Pravdinsk (“Noidam”), Svetly (“Bravo Casaro”). The Lithuanian cuisine shop “Shakotis” in Zelenogradsk makes Sakotis, a national Lithuanian cake, while regional gastronomic fairs sell Kurteshkalach, a Hungarian pastry. Kaliningrad confectioners selling products through social networks offer a wide variety of European pastries. However, these goods might be similar to “sanctioned” products in terms of quality but not price.

The situation with phasing out “sanctioned” fruit and vegetables is different. The measures introduced to replace prohibited imports with local products led to the saturation of the Kaliningrad market with products generally similar to the imported ones in both quality and price. The measures included planting several industrial apple orchards in the region, opening new large greenhouse facilities for year-round production of vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, salad plants, herbs) and berry plantations, and creating the Kaliningrad Fruit Nursery.

Consumer preferences in food products and cross-border mobility after 2014. According to the conducted sociological study, until 2014, 58 % of the Kaliningrad region’s population consumed food products whose import into Russia was prohibited under the embargo; 44.8 % of respondents said that the sanctioned goods had accounted for a small part of their grocery basket; 13.1 % of respondents state that such products dominated their purchases in the corresponding niches. Until 2014, the practice of buying products under embargo was more common among the region’s residents aged 25—54 years in good or very good financial standing. In terms of their occupation, these were experts and managers (chief executives, entrepreneurs, heads of departments). The low popularity of such practices among military and law enforcement personnel seems understandable as there are restrictions on their cross-border travel.

Spatial differentiation in the importance of “sanctioned” products is mostly insignificant: the share of those who consumed such products ranges from 51 to 54 % everywhere, except for Kaliningrad (64 %) and the areas bordering on Poland (41 %). A possible explanation for the increased share of consumption of “sanctioned” products in the areas bordering on Lithuania might be their ethnic composition and a pedestrian border crossing point in Sovetsk. Traditionally, Lithuanians living in the region concentrate in Kaliningrad (18 %, according to the 2010 national census) and municipalities bordering on Lithuania (51 %). In these areas, there are enterprises under the Lithuanian jurisdiction (for example, Viciunai-Rus LLC) attracting temporary workers, and migrants from the neighbouring republic. The popularity of Lithuanian goods among them is higher. In the case of Kaliningrad, this is due to the greater population mobility, which is generally characteristic of residents of large cities. In the border municipality of Bagrationovk, through which the main motorways to Poland go and where there are several road border crossing points, more than three-quarters of the population live in rural areas and do not have ample opportunities to travel abroad. According to the survey, until 2014, more than 40 % of residents of rural areas of the Kaliningrad region did not buy products covered later by the embargo (33 % of residents of urban areas). However, one of the probable explanations for this is the unwillingness of the respondents living in the borderland with Poland to answer questions about the purchase of Polish goods honestly, especially when it came to illegal imports<8>.

The majority of residents who were previously reliant on prohibited food imports had to make significant changes to the range of products they consumed. Adjusting to the restrictions increased the consumption of Russian (20.6 % of respondents) and Belarusian products (31.4 %), and led to the elimination of certain products not having high-quality analogues (14.8 %).

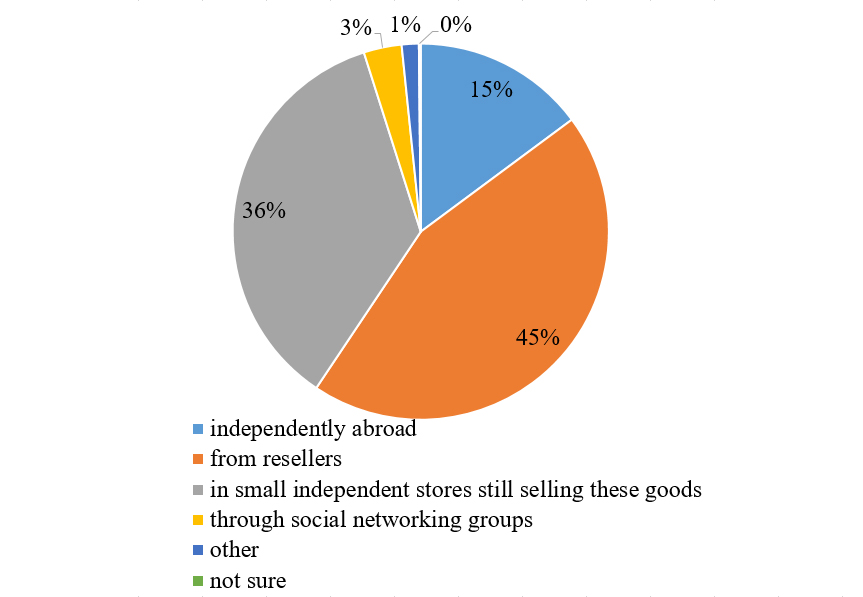

In the Kaliningrad region, a high share of the population (43 % of respondents) continued buying prohibited imports despite the food embargo. They purchase them through different channels (Fig. 2): most often, residents of the Kaliningrad region buy what they need either from private sellers (45 %) importing products from Poland “for personal consumption” in large volumes or in small private stores (36 %) illegally selling such products. At the same time, buying from resellers is almost the only opportunity to purchase the necessary goods in the municipalities remote from the border with Poland, i. e. the Neman, Nesterov, Slavsk, Polessk, Chernyakhovsk districts, as well as in the Gusev district located relatively close to the border with Poland. More than 70 % of people buying prohibited products made purchases this way. Purchasing in small private stores is most typical for residents of cities (Kaliningrad, Sovetsk) and municipalities gravitating to the Kaliningrad agglomeration (Guryevsk and Zelenogradsk municipal districts), Baltiysk city district. Residents of the districts on the Polish border tended to shop for groceries abroad while travelling independently: these are Bagrationovsk (42 %), Gusev (24 %), and Guryevsk (37 %) districts.

There are several reasons for the sustainability of consumer preferences noted above. According to the respondents, the major ones are the quality of imported products and personal taste preferences. The lack of similar products in the local market is in the third place. Lower price is only the fourth leading reason. At the same time, people with different income levels stated different reasons for buying “sanctioned” food. Residents in bad and very bad financial standing were much more likely to buy “sanctioned” goods due to their low cost (18 % versus 13 % for the sample). Kaliningraders characterizing their financial situation as good or very good placed higher importance on the width of the range of “sanctioned” products.

|

| 2 |

|

Ways to purchase “sanctioned” goods in the Kaliningrad region |

|

|

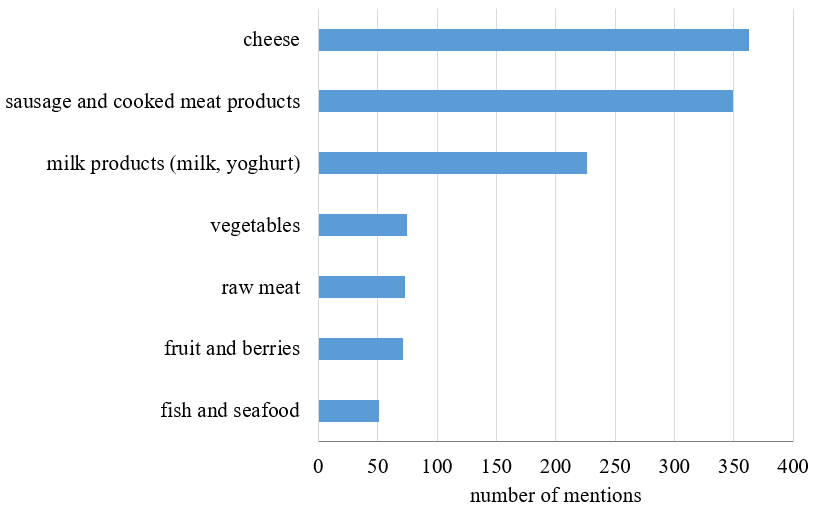

According to the study, residents of the Kaliningrad region demonstrate a high level of loyalty towards certain categories of “sanctioned” products. These include cheeses, sausages, other meat products, and milk products (Fig. 3). This clearly correlates with the level of the region’s self-sufficiency in these goods. The least important for the respondents are imported fish and seafood. Their production in the region is considered excessive: 300,000 tons per year with consumers’ consumption of 20,000 tons per year.<9> At the same time, according to our previous calculations, food self-sufficiency, for instance, in milk and dairy products is 76 %, which is low considering the “doctrinal” threshold of 90 % [14].

|

| 3 |

|

“Sanctioned” goods that residents of the Kaliningrad region continued to buy after 2014 |

|

|

Respondents in the region also highlighted that the food embargo had a notable effect on encouraging some residents to engage in farming and home-production of certain food items such as cheese, cottage cheese, and bread. However, such strategies are rare.

Approximately half of the respondents observed a significant increase in the volume and variety of products available in stores, as well as the emergence of new local manufacturers in the Kaliningrad region. The changes regarding food from other regions of Russia and countries not subject to sanctions are more subtle. A significant proportion of respondents, around a quarter, noted an increase in the availability of Belarusian products in retail outlets. A large group of respondents mentioned the increase in the range of food products from Kazakhstan. However, this is primarily confectionery products not covered by the food embargo.

One of the major changes in the food market, mentioned by 83.3 % of residents of the Kaliningrad region, is the increase in prices for items banned from import. At the same time, these changes were most significant for residents characterizing their financial situation as bad or very bad (42 % of respondents in this category); 61 % of respondents believe that good quality products at competitive prices disappeared after 2014; 34 % noticed goods produced in Russia under well-known foreign brands banned from import; 33.8 % expressed the opinion that the range of niche products (delicacies, dietary products, lactose-free milk) has significantly decreased or completely disappeared.

One of the questions asked the respondents to name brands or manufacturers in some product niches (“sanctioned” ones) currently dominating their purchases. There are two distinct trends for milk products. The first is the loyalty to local producers with the absolute dominance of products by “Zalessky Fermer”, which has tremendously increased production capacity and volume after the introduction of the food embargo. The second is the focus on Belarusian producers who flooded the market holding a dominant position in cheeses.

The preferences in sausage and meat products are more diversified. A distinctive feature is the continued strong loyalty to Polish products. That correlates with the situation in the meat industry (production of sausage and meat products), whose development has been hampered since 2014 by the disruption in cross-border trade in raw materials and insufficiency of own raw materials, despite the growth in meat production.

The number of people who found it difficult to answer the question about fruit and vegetable producers is so large that it does not allow drawing statistically significant conclusions about preferences in this category. Presumably, the population does not pay much attention to the manufacturer in these product categories focusing more on “what is available”, appearance and price.

One of the typical consumer behaviour strategies for a borderland is independent shopping trips to neighbouring countries. According to the survey, 35.7 % of the Kaliningrad region’s population visited Poland, and 17.8 % — Lithuania. High travel intensity (once a month or more) is typical for 11.4 and 3.4 % of the population, respectively.

Among the purposes of trips to Poland, the first place is shared by leisure (visiting museums, cafes, cultural events, and attractions) and food shopping. In trips to Lithuania, the latter was not so popular due to the higher cost of products.

Among the cross-border practices, the centre-peripheral gradient is clearly expressed while the factor of the immediate neighbourhood is not much manifested. The population characterized by such mobility resided mainly in Kaliningrad and the surrounding Guryevsk municipal district. Interestingly, grocery shopping trips were most often associated with a bargain price. At the same time, the most affluent population of the region mainly resides in Kaliningrad and its suburbs. The combination of factors is quite curious: higher incomes, greater mobility and a more pronounced desire to save on grocery shopping. At the same time, very few respondents in the municipalities bordering Poland shopped there regularly. Possible reasons for this have been mentioned above.

Generally, across the sample, respondents who visited Poland mostly rated their financial situation as average, suggesting that in many ways such trips were a means of saving rather than satisfying taste needs.

Among the population who were regular travelers to Poland before the borders closed due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, 53 % of respondents indicated a decline in the frequency of their trips from year to year. According to their feedback, the most significant reason for this decline was the decreasing benefits of such trips, primarily influenced by the changing exchange rate of the Russian ruble against the Polish currency. The growth in associated costs (insurance, visa) and decreased incomes were also important. Another factor was the abolition of the LBT regime. A small number of respondents reported that they had stopped their trips to Poland because they believed it had become impossible to bring food across the border. However, it is important to note that the 2014 food embargo did not restrict the transportation of products for personal consumption.

Conclusions

One of the main effects of the food embargo on consumers in Russia was the increase in food prices. The interior regions responded with an increase in consumer spending, a reduction in consumption, or a change in the food basket in favour of a cheaper segment. This study shows that the residents of the Kaliningrad region additionally had the fourth option: they could continue purchasing “sanctioned” goods abroad or from resellers. Such a strategy underwent some changes between 2014 and 2021.

Significant cross-border price gradients generally made food shopping in Poland profitable until 2019, but the benefits were declining due to negative changes in exchange rates. Nevertheless, buying Polish cheese, milk, sausages and other products was much cheaper. In contrast, the profitability of buying fruit and vegetables fell due to the increase in local production.

Until 2014, almost 60 % of the Kaliningrad region’s population consumed products banned from import. Although statistical analysis records the financial profitability of such purchases, the survey data show that the share of those who purchased “sanctioned” goods is higher among the residents in good and very good financial standing. A unique situation for Russia is the fact that at least until the COVID-19 pandemic, 43 % of exclave residents continued to buy products covered by the import ban.

The range of ways to purchase “sanctioned” products decreases along the centre-periphery axis. Residents of Kaliningrad and the suburbs buy food products while travelling abroad, from “resellers”, in small independent stores. In remote municipalities, there is only one opportunity — buying from “resellers”. The closeness to the Polish border predictably plays its role: the frequency of cross-border food shopping trips is higher here than in most other municipalities.

The role of “sanctioned” goods in consumption fully correlates with the region’s self-sufficiency in certain items. The lower the self-sufficiency and the deeper the problems in the industry, the higher the importance of Polish goods in consumption. However, a similar thesis applies to products from other regions of Russia and Belarusian products that flooded the market after 2014.

This study shows that, after 2014, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the frequency of cross-border trips was steadily declining due to falling incomes and the depreciation of the ruble. Nevertheless, a third of the Kaliningrad region’s residents visited Poland occasionally, shopping for groceries, often combining it with tourist trips.

The study was financially supported by the RFBR, project № 20-05-00739. The analysis of the population’s cross-border practices was carried out with the support of the RSF project “Effects and functions of borders in the spatial organization of Russian society: country, region, municipality” (№ 22-17-00263).