Population change and the settlement system transformation in Poland, as revealed by the 2021 census

- DOI

- 10.5922/2079-8555-2023-2-3

- Pages

- 41-61

Abstract

This article aims to analyse current geodemographic changes in Poland, based on the data of the 2021 National Population and Housing Census. Methods, traditional for socioeconomic geography, such as zoning, were employed. Poland’s population decreased during the inter-census period (2011—2021), with the urban population declining faster than its rural counterpart. The large voivodeships aligned along the Vistula ‘axis’ — Mazowiecka, Lesser Poland and Pomerania — outperform other Polish regions in geodemographic terms. The situation is relatively favourable in Greater Poland, where the country’s main motorways converge. Districts and voivodeships where the geodemographic situation is more vulnerable can be divided into two groups: depressed and backward. The first one includes the traditionally industrial voivodeships of Southern and Central Poland; the second mainly consists of eastern voivodeships. The population decline in Eastern Poland is gathering pace: the 2021 census shows, a more or less favourable geodemographic situation is observed only in the main eastern cities and their environs. This state of affairs is largely due to the Polish government deliberately halting cooperation with Russia and Belarus, including cross-border collaborations. Yet, this decision seems to create more problems for Poland than its eastern neighbours. If the current trends persist, the eastern voivodeships, the stronghold of the right-wing conservatives in power, may not only rapidly lose population but also face a reduction in the level of socioeconomic development.

Reference

Introduction

In the second and the beginning of the third decade of the 21st century, the population structure in Europe underwent significant changes. Many countries experienced a combination of positive net migration and natural population decline. The positive net migration was influenced by both legal and illegal migration from Asian and African countries, while the natural decline was primarily attributed to the ageing population in most European countries.

Although these geodemographic transformation trends were general for Europe, there were significant variations across its different regions, including Northern, Western, Southern, and Eastern Europe, as well as across individual states and regions within them. The geodemographic changes in the post-socialist countries of Eastern Europe appear particularly interesting. In the 30 years since the demise of the USSR and the ‘socialist camp’ led by it, the paths of the former ‘states of real socialism’ have diverged widely. Many of the processes that we have witnessed and are witnessing now in the former socialist countries are also taking place in the states that emerged on the former territory of the Soviet Union, including Russia.

The demographic processes in Poland require special attention. The country is the largest post-socialist state in Eastern Europe in terms of area and population, and it has a long common border with the post-Soviet countries of Russia, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. Moreover, there are clear similarities in the political transformation of the Republic of Poland and the Russian Federation. Since the PiS party (Pol. “Prawo i Sprawiedliwość”, Eng. “Law and Justice”) came to power, Poland has aligned its foreign and domestic policy with the values that are traditionally important to Polish society, as perceived and interpreted by the leaders of the Law and Justice (PiS) party. The foreign policy approach of the PiS is rooted in the belief that Poland is surrounded by adversaries, with Russia being the primary concern. Similarly, Russian foreign policy is shaped by the perception that the country is encircled by enemies, with NATO being identified as its largest adversary, and Poland’s membership in the alliance playing a significant role in this context. In the domestic policies of both countries, Poland and Russia, there are notable similarities. In Poland, there is a strong emphasis on demographic policy, often referred to as ‘political demography’, which prioritizes family values rooted in religious foundations. Similarly, in Russia, there is a focus on addressing demographic challenges through government initiatives aimed at increasing fertility rates. Both countries perceive government investment and support for family and fertility as key approaches tackling their demographic issues. Poland has the 500+ policy [3], while Russia has its maternity (family) capital policy. At the same time, birth rate stimulation in Poland also has a repressive component. They limit abortion penalizing providers,<1> which is not yet the case in Russia.

The demographic processes in Russia and Poland are also similar. Both countries see a decrease in population, mainly due to its natural decline. Although for several years after joining the European Union, Poland experienced a period of growth in the birth rate, defined as a “euro-baby boom” [4], this quickly passed. In addition, being an EU member, Poland experiences a large outflow of labour [5].

The National Population and Housing Census (Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań, hereinafter referred to as NSP 2021) was held in Poland between April 1st and September 30th 2021. In contrast to Russia, in Poland, participation in the census is mandatory, residents must give accurate, comprehensive and relevant answers to the census questions. Providing incorrect information can result in a fine or imprisonment for up to two years, refusal to provide the information required for the census is punishable by a fine, a fine is also imposed for failure to comply with the deadlines for providing the information (paragraph 1, Art. 28, as well as Art. 56—58 of Act on Official Statistics).<2> NSP 2021 data were collected online, through phone interviews with either a citizen calling a special line or census takers (pol. — rachmistrzów spisowych) calling a citizen, as well as through face-to-face interviews conducted by enumerators visiting people’s homes. Thus, the NSP 2021 data appear to be complete and reliable, allowing for an objective assessment of the current geodemographic processes in Poland.

Statistics Poland (Główny Urząd Statystyczny, hereinafter referred to as GUS) published preliminary census results from February to December 2022. At the time of writing this article (early 2023), the latest report was the one released on December 21st, 2022. Called “Ludność rezydująca — informacja o wynikach Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2021” (“Permanent population — information on the results of the National Population and Housing Census 2021”), it was the first one providing finalised census results.<3>

This article aims to analyse current geodemographic changes in Poland, based on the data of the 2021 National Population and Housing Census.

Materials and Methods

The main method employed in the research is statistical. The principal data source is the NSP 2021 reports published by GUS in 2022. The study also uses descriptive, classification and zoning methods conventional for economic and geographical research.

Results

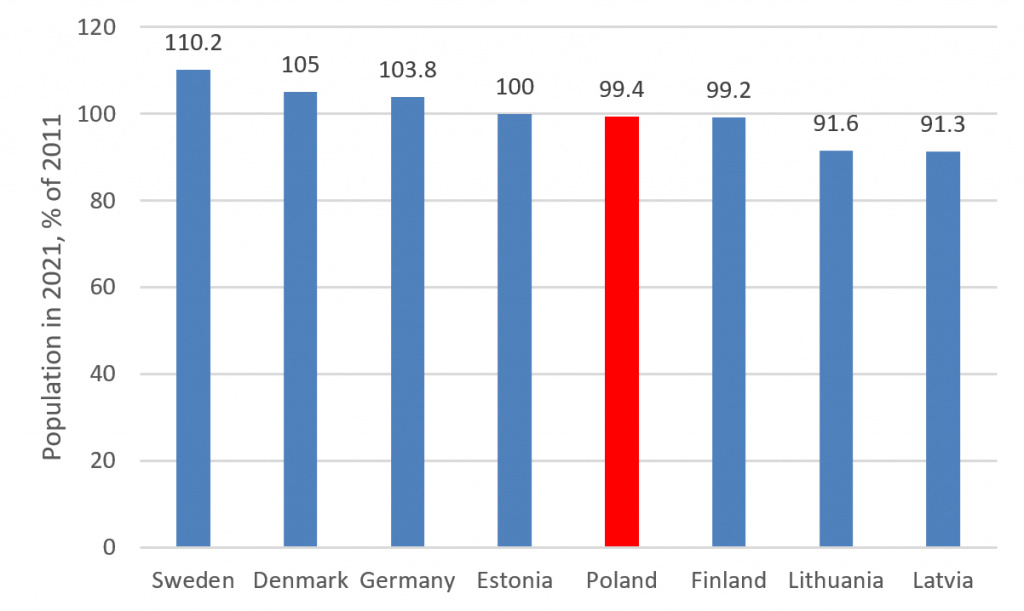

The main result of any population census is the identification of the major trends in population change. In general, in the inter-census period (2011—2021), Poland’s present population decreased. As of March 31st, 2021, it was 37,019,327 people, or 97.2 % of the population in 2011 (38,044,565 people<4>), which slightly differs from the current Eurostat data (Fig. 1).

|

| 1 |

Changes in the population of EU countries in the Baltic macroregion, percentage of 2021 to 2011 population |

Compiled from: Population change — Demographic balance and crude rates at the national level, 2022, Eurostat, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_gind/default/table?lang=en (accessed 14.02.2022).

The number of men (17.9 million in 2021, 18.4 million in 2011) and women (19.1 million in 2021, 19.6 million in 2011) both decreased by approximately 0.5 million (the approximation is the result of the rounding). Thus, we can assume that the main reason for the decrease in Poland’s population between 2011 and 2021 was its natural decline (Table 1).

Year | Migration gain | Birthrate | Mortality | Natural increase | Total gain |

2011 | – 0.3 | 10.2 | 9.9 | – 0.3 | 0 |

2021 | 0.1 | 8.8 | 13.8 | – 5 | – 4.9 |

Compiled from: Population change — Demographic balance and crude rates at the national level, 2022, Eurostat, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_gind/default/table?lang=en (accessed 14.02.2022).

If negative net migration had had a major part in population decline, the number of representatives of one sex would have decreased faster than the other. These processes predominantly involve men, although in today’s post-industrial countries of “United Europe,” it is challenging to determine whether male or female occupations are in higher demand. The same applies to labour immigration to Poland, mostly from the East, mainly Ukraine, predominantly its Western part [6] (Table 2).

Country | Migration gain | Birthrate | Mortality | Natural increase | Total gain |

2021 | |||||

Germany | 3.6 | 9.6 | 12.3 | – 2.7 | 1 |

Poland | 0.1 | 8.8 | 13.8 | – 5 | – 4.9 |

Sweden | 4.9 | 11 | 8.8 | 2.2 | 7 |

Denmark | 4.6 | 10.8 | 9.8 | 1 | 5.7 |

Finland | 4.1 | 9 | 10.4 | – 1.4 | 2.6 |

Lithuania | 12.4 | 8.3 | 17 | – 8.7 | 3.7 |

Latvia | – 0.2 | 9.2 | 18.4 | – 9.2 | – 9.3 |

Estonia | 5.3 | 10 | 14 | – 4 | 1.3 |

2011 | |||||

Germany | 3.7 | 8.3 | 10.6 | – 2.3 | 1.3 |

Poland | – 0.3 | 10.2 | 9.9 | – 0.3 | 0 |

Sweden | 4.8 | 11.8 | 9.5 | 2.3 | 7.1 |

Denmark | 2.4 | 10.6 | 9.4 | 1.2 | 3.6 |

Finland | 3.1 | 11.1 | 9.4 | 1.7 | 4.8 |

Lithuania | – 12.6 | 10 | 13.6 | – 3.6 | – 16.2 |

Latvia | – 9.7 | 9.1 | 13.9 | 4.8 | – 14.5 |

Estonia | – 2.9 | 11.1 | 11.5 | – 0.4 | – 3.3 |

Compiled from: Population change — Demographic balance and crude rates at the national level, 2022, Eurostat, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_gind/default/table?lang=en (accessed 14.02.2022).

Between 2011 and 2021, the proportion of the urban to rural population was changing with a slight increase in the share of the latter. Poland’s urban population was 23.1 million people, comprising 60.8 % of its total population, in 2011, it decreased to 22.2 million people in 2021, 59.9 % of the total population. The rural population was 14.9 million people in 2011 (39.2 % of the total), and 14.8 million people in 2021 (40.1 % of the total). Thus, with the total population falling by about 1 million people between 2011 and 2021, Poland’s urban population decreased by about 900,000, and the rural population by 100,000 people.

Identifying the causes and consequences of ruralization is a challenging task, especially considering that it is relatively uncommon in European countries. However, Poland has experienced a decline in its urban population since the end of the 20th century [7]. While urbanization has been a characteristic trend in most European states for centuries, Poland has lagged behind many of them in terms of its level and pace, largely maintaining its identity as a predominantly rural country. Similar to Russia, a significant portion of the urban population in Poland consists of individuals who are first- or second-generation city dwellers and may not be fully accustomed to urban lifestyles.

In Poland, the challenges of urban lifestyle development can be attributed, in part, to the historical process of the country’s territorial formation during and after World War II. The country lost a large part of the Second Polish Republic (interwar Poland), while it obtained some new lands in the north and west (the so-called Recovered Territories, Pol. Ziemie Odzyskane), where a large share of the population was displaced both from the central regions severely damaged during the war and from the former eastern outskirts of the Second Polish Republic, which became part of the USSR (to the Ukrainian SSR and the BSSR). This displaced population settled primarily in the cities. According to Zhirov, “the incorporation of highly urbanized Western lands into the Polish state significantly increased the general level of the country’s urbanization. Peasants, the majority of the migrants, had to adjust to city life” [9, p. 85]. The path for the rehabilitation of rural areas in the north and west of present-day Poland was creating large agricultural enterprises on vast tracts of land [10] mainly relying on urban settlements abandoned by Germans. Those who have worked and continue to work in these enterprises have been and remain agricultural workers rather than peasants dominating eastern Poland. An integral part of ruralization in the country is suburbanization, with new urban quarters built outside cities in formally rural areas. We can call it “false ruralization” by analogy with “false urbanization”.

Another probable reason for the decline in the number and proportion of the urban population is the increase in the number of homeless, former city dwellers leaving their permanent residence and moving “to nowhere”. Homelessness is a big problem in Poland. However, it has become so commonplace, just like in Russia, that only its extreme cases get attention. For instance, in November 2022, wide media coverage was given to a story about a mother with a two-year-old daughter found living in a tent in the coastal forest belt near Gdansk.<5>

According to Fedorov, “the geodemographic characteristics of regions affect the direction and rate of their socioeconomic development, whereas the emerging disparities between the actual living standards and the desired course of regional development can aggravate existing economic and social problems” [11, p. 7]. Characterizing the territorial differentiation of the geodemographic development in the Baltic region, Kuznetsova and Fedorov correctly state that “in highly developed regions demographic indicators are better” [12, p. 136]. The reverse is also true: the better the region’s demographic indicators, the healthier its economic and social development is. Comparing changes in the voivodeships’ population against their gross regional product per capita confirm this assumption [13].

Spatial differences in the geodemographic development of Poland are striking.

EU statistics distinguishes seven NUTS 1 regions in Poland: PL9 (Makroregion województwo mazowieckie (Masovian Voivodeship Macroregion) consisting of Warsaw Capital region and Masovian Region), PL6 (Makroregion północny (Northern Macroregion) with Kuyavian-Pomeranian, Warmian—Masurian, Pomeranian Voivodeships), PL5 (Makroregion południowo-zachodni (South-Western Macroregion) with Lower Silesian and Opole Voivodeships), PL4 (Makroregion północno- zachodni (North-Western Macroregion) with Greater Poland, West Pomeranian and Lubusz Voivodeships), PL8 (Makroregion wschodni (Eatern Macroregion) with Lublin, Podlaskie, Subcarpathian Voivodeships), PL2 (Makroregion południowy (Southern Macroregion) with Lesser Poland and Silesian voivodeships), PL7 (Makroregion centralny (Central Macroregion) with Lodz and Holy Cross Voivodeships).

The territories within the NUTS 1 regions of Poland display notable demographic, social, and economic diversity. It seems that in some cases, the composition of these units was divided mechanically by the EU statistics service, without fully accounting for the unique characteristics and dynamics of the country’s territory. For example, the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship geodemographically (and in other ways) has much more in common with the Podlaskie Voivodeship (its principal city is Bialystok) than with the Pomeranian Voivodeship (Gdansk) even though it shares a common history with the latter (before World War II this territory was part of Germany). Indeed, besides their geographical proximity to the eastern border of Poland, the Podlaskie and Subcarpathian voivodeships in the PL8 “Makroregion wschodni” exhibit notable differences in various aspects. These differences encompass nature, demography, and economy, among other factors. The natural environment, including landscapes, climate, and ecological features, can vary significantly between the two regions. Additionally, demographic characteristics such as population size, composition, and migration patterns can differ substantially. Two voivodeships on the shore of the Baltic Sea, the Pomeranian and the West Pomeranian, belong to different NUTS1 regions, the Northern and the North-Western, respectively. The name “centralny” (Central) seems somewhat inappropriate for a macroregion consisting of the Lodz (its principal city is Lodz) and the Holy Cross (Kielce) voivodeships since neither of them is in any sense “central”. Lodz, once a developed textile centre, is an old industrial city in deep decline. Kielce is just a backward city that never knew much prosperity.

Considering geodemographic, natural, transport and other factors and using the basin principle of zoning, the authors distinguish other regions than those in the NUTS grid. They can be called geodemographic areas: Capital (Masovian Voivodeship with the middle reaches of the river Vistula as the axis), Coastal (Pomeranian and West Pomeranian voivodeships with the Baltic Sea coast as the axis), Warta (Greater Poland and Lubusz voivodeships with the river Warta running into the Oder in its middle reaches as the axis), Silesian (Lower Silesian, Opole, Silesian voivodeships with the Oder in its upper reaches as the axes), Precarpathian (Lesser Poland, Holy Cross and Subcarpathian voivodeships with the upper reaches of the Vistula and its tributary the San as the axis), Bug-Masurian (Lublin, Podlaskie and Warmian-Masurian voivodeship, the axis in its southern part is the Bug, in its western part there is a watershed between the basins of the Vistula and the Neman and the Pregol, which is the Masurian lakes), and Vistula-Oder (Kuyavian-Pomeranian and Lodz voivodeships with the watershed between the Vistula and the Oder, and the lower reaches of the Vistula) (Table 3).

Geodemographic area | Population, thousand people | 2021, % of 2011 | |

2011 | 2021 | ||

Capital | 5,286 | 5,513 | 104 |

Coastal | 4,007 | 4,009 | 100 |

Warta | 4,478 | 4,486 | 100 |

Silesian | 8,557 | 8,242 | 96 |

Precarpathian | 6,754 | 6,704 | 99 |

Bug-Masurian | 4,826 | 4,562 | 95 |

Vistula-Oder | 4,632 | 4,413 | 95 |

Compiled from: Ludność rezydująca — informacja o wynikach Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań, 2022, Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny, URL: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-rezydujaca-dane-nsp-2021,44,1.html (accessed 14.02.2023).

During the inter-census period, it is noteworthy that only one geodemographic area, specifically the Capital area (also referred to as NUTS 1 PL9 Makroregion województwo mazowieckie), experienced a population increase among the seven areas identified by the authors. However, this growth was mainly due to Warsaw. While in the capital the population grew by 10 %, in the rest of the voivodeship by 2 %, and this growth was in the suburbs of Warsaw. A significant part of the Masovian Voivodeship, mainly its northern and eastern counties (powiats) showed a decrease in population. In the Coastal and Warta regions in the north and north-west of Poland, the population remained approximately the same. In all the other geodemographic areas, the population has declined. The smallest decrease (by 1 %) was in the Precarpathian region (southeast of Poland). The population in the Silesian region in southwestern Poland decreased by 4 %. The biggest reduction (by 5 %) was reported in the Bug-Mazurian and Vistula-Oder regions located to the west and east of the Capital region.

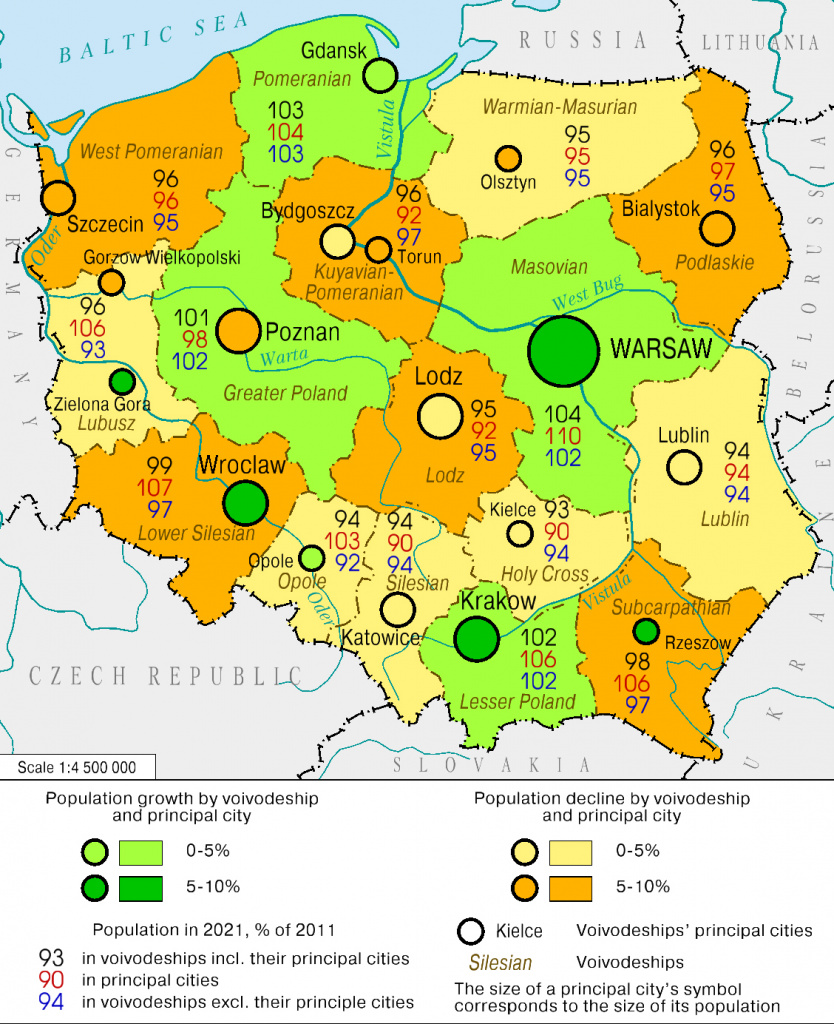

In terms of the combination of demographic trends in the voivodeships and their principal cities, all the voivodeships can be divided into the following groups:

— voivodeships with the population increasing in both the voivodeships and their principal cities;

— voivodeships with the population declining in general but growing in their principal cities;

— voivodeships with the population growing in voivodeships in general and declining in their principal cities;

— voivodeships with the population declining both in the voivodeships and in their principal cities (Fig. 2).

|

| 2 |

| Changes in resident population by voivodeships and their principal cities, 2011—2021 |

Compiled from: Ludność rezydująca — informacja o wynikach Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań, 2022, Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny, URL: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-rezydujaca-dane-nsp-2021,44,1.html (accessed 14.02.2023).

The population growth of some principal cities is due to the incorporation of the adjacent settlements. For instance, one of the two principal cities in the Lubusz voivodeship, reported a decrease in the population (in 2021 it was 96 % of its 2011 size), while the other, Zielona Gora, showed an increase (in 2021 it was 116 % of its 2011 size). The demographic trends in both the Lubusz Voivodeship in general and in these cities would have been the same, but on January 1st, 2015, Zielona Gora incorporated a suburban rural gmina with the same name, which technically increased its population. The expansion of the urban area contributed to the growth of the population of Krakow (in 2013, it incorporated part of the gmina Kocmyrzow-Luborzyca) and Opole (in 2017, it incorporated parts of the gmina Dabrowa, Dobrzen Wielki, Komprachcice and Pruszkow). The territory of Rzeszow expanded three times in that period: it incorporated part of the gmina Swilcza in 2017, part of the gmina Glogow Malopolski and Tyczyn in 2019, part of the gmina Glogow Malopolski in 2021). Due to the expansion of the urban area, the population decline rate in Szczecin has formally decreased, since in 2017 it incorporated the gmina Goleniow<6>.

As mentioned earlier, the Masovian Voivodeship and its principal city, Warsaw, are among the regions and cities in Poland experiencing population growth. In the north of Poland, it is the Pomeranian Voivodeship with Gdansk as its principal city. In the inter-census period, its total population grew by 3 %, and the population of Gdansk by 4 %. The basis of the settlement system of the Pomeranian Voivodeship is Tri-City (Pol. Trójmiasto). It is three practically merged cities: the port of Gdansk (formerly German Danzig), the port-industrial Gdynia, built in the interwar period as the only then Polish port on the Baltic Sea, and the resort Sopot, located between them [14]. The population in Tri-City is growing due to both positive net migration and natural growth [15].

In the south of Poland, one of the voivodeships where both the total and principal cities’ populations grew, is the Lesser Poland Voivodeship (Krakow). Such voivodeships are the most prosperous not only from a geodemographic but also from a socio-economic perspective. The Masovian, Pomeranian, and Lesser Poland voivodeships, along with Greater Poland, have consistently been at the forefront in terms of quality of life for several decades [16] (Table 4).

Voivodeship | GRP per capita in 2021, % | Population in 2021, % of 2011 |

Masovian | 158.6 | 104 |

Lower Silesian | 109.6 | 99 |

Greater Poland | 108.6 | 101 |

Voivodeship | GRP per capita in 2021, % | Population in 2021, % of 2011 |

Silesian | 100.7 | 94 |

Lodz | 97.2 | 95 |

Pomeranian | 94.2 | 103 |

Lesser Poland | 90 | 102 |

West Pomeranian | 84.6 | 96 |

Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 82.1 | 98 |

Lubusz | 82 | 96 |

Opole | 79.8 | 94 |

Podlaskie | 74.1 | 96 |

Holy Cross | 73.1 | 93 |

Warmian—Masurian | 71.3 | 95 |

Subcarpathian | 69.4 | 98 |

Lublin | 69.2 | 94 |

Compiled from: Regions in Europe. 2022 interactive edition, 2022, Eurostat, URL: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/regions/#total-population (accessed 14.02.2023).

The coefficient of linear correlation between the GRP per capita in 2021 and the population changes between 2011 and 2021 is 0.65, i. e. the relationship between them is close to significant.

It should be noted that it was in the geodemographically most prosperous voivodeships where the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic were most pronounced [17]. In the same manner, Russian well-off regions suffered greater than the others from the pandemic consequences [18], [19]. However, the pandemic had not considerably changed the demographic situation either in Poland or Russia.

There are four voivodeships in Poland where the total population is decreasing while their principal cities’ population is growing: Lubusz, Lower Silesia, Opole, and Subcarpathian. The first three are a vast area of land on the Oder. In the Lubusz Voivodeship, the increase in the population of its two principal cities, Zielona Gora, as noted above, is largely formal: the city’s population grew due to the incorporation of suburban areas. The Lower Silesian Voivodeship (its principal city is Wroclaw) and the Opole Voivodeship (Opole), saw population redistribution.

Economically, the cities of Lower Silesia have a strong reliance on mining and primary processing industries. For example, the Legnica-Gloga copper district (pol. Legnicko-Głogowski Okręg Miedziowy, LGOM) occupies a significant part of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship which geographically largely coincides with the Legnica Voivodeship existing between 1975 and 1998. The then division into voivodeships, much more fractional than the current one, generally corresponded to Poland’s economic and geographical zoning. The principal city of this area is Legnica, the command and a large garrison of the Soviet Northern Group of Forces were located from 1945 to 1993 [20]. A copper plant (Pol. Huta Miedzi Legnica), built in 1951—1953 with the technical assistance of the USSR, was the second city-forming enterprise until 1993. Upon the withdrawal of Soviet (Russian) troops from Poland, it became the first one. This enterprise is quite successful, its production is growing, especially quickly after the 2019 ceremonial launch of a tilting rotary furnace for copper scrap by the current Prime Minister of Poland Mateusz Morawiecki.<7> At the same time, the shift to recycling and use of scrap has led to a decrease in the use of products of mines in the LGOM, and, as a result, to a decrease in jobs both there and in the copper plant due to the growth in productivity with the introduction of new equipment. Thus, the improving economic performance of the city-forming enterprise contributed to the deterioration of the demographic situation rather than its improvement. In 2011, the population of Legnica was 103,000 people, while in 2021, it was 94,000 people. The population of the Legnica-Glogow subregion (generally coinciding with the LGOM) of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship amounted to 454,000 in 2012, and 434,000 in 2021. This is not the evidence of Legnica “spreading” to its surrounding gminas and counties, but the evidence of the population outflow from the economically growing area.

In this case, Legnica serves as an example, but similar geodemographic changes can be observed in other cities and towns in the Lower Silesian and Opole voivodeships. It seems that a portion of the population leaving cities and towns similar to Legnica in Lower Silesia chooses to leave the region, and sometimes even Poland, while another portion settles in the principal cities of the voivodeships, contributing to their population growth.

In the Subcarpathian Voivodeship, the increase in the population of its principal city, Rzeszow, just like in Zielona Gora in the Lubusz Voivodeship, is largely formal and stems from the merging with its suburban areas. At the same time, Rzeszów is the first major Polish city on the path of Ukrainian labour migration to Poland, which also contributes to the growth of its population (migration from Ukraine related to the military events that began in February 2022 is not the subject of this article).

One of the voivodeships with the total population growing and the principal cities’ population decreasing is the Greater Poland Voivodeship with its centre in Poznan. This geodemographic transformation results from the fact that the determining factor in the economic development of the modern Greater Poland Voivodeship is its economic and geographical position. Two of Poland’s key motorways go through it: the latitudinal one connecting Western Europe with Belarus and Russia and the longitudinal one connecting the Polish ports on the Baltic Sea with the Czech Republic and the more southern states of the European Union. Such a favourable economic and geographical location has naturally attracted industries, and Poznan was not the only industrial centre of Greater Poland.

The second most populous city, Kalisz, was and still is one of the centres of the Polish aircraft industry. Here, in the 1970—1990s, under Soviet license and in cooperation with the USSR, the aircraft factory PZL-Kalisz produced An-2 (“corn crop dusters”), as well as engines for them. They still produce these engines, as these aircraft still fly around the world. Since 1992, there is also Pratt & Whitney Kalisz producing aircraft engines for Airbus and Bombardier. In Poznan, the old industrial centre of the voivodeship, the closure of factories that existed before the 1990s and the decline in manufacturing employment led to a decrease in population. However, new industrial enterprises have emerged in the suburban areas adjacent to Poznan, which are part of the larger Poznan agglomeration. As a result, the decline in population in Poznan is primarily a formal one, as the city’s influence and urban development extend beyond its immediate boundaries and encompass the surrounding territory.

The largest group of voivodeships is the one in which both the overall population and the populations of the principal cities have decreased. These include the West Pomeranian Voivodeship (with its centre in Szczecin), the Silesian Voivodeship (Katowice), the Holy Cross Voivodeship (Kielce), the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (Olsztyn), the Podlaskie Voivodeship (Bialystok), the Lublin Voivodeship (Lublin), the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship (Bydgoszcz, Torun) and the Lodz Voivodeship (Lodz).

A decrease in both the total population and the populations of the principal cities seems to indicate a generally unfavourable socio-economic situation in the region. However, the reasons for this disadvantage vary. There are two subgroups within this group of voivodeships. The first is depressed voivodeships whose population decline is associated with a reduction or even cessation of old industries and slow development of new ones or their absence. The second subgroup is backward voivodeships traditionally developing more slowly than Poland in general.

Depressive voivodeships include the West Pomeranian, Silesian, Lodz and Kuyavo-Pomeranian. Backward ones include the Holy Cross, Warmian-Masurian, Podlaskie and Lublin. The decline in the population of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship is due to its rapid deindustrialization. For instance, Szczecin’s largest enterprise that existed since German times, the former shipbuilding plant named after Adolf Varsky (Stocznia Szczecińska im. Adolfa Warskiego), which built its last vessel (FESCO Vladimir) for the Far Eastern Shipping Company in 2009, and the Szczecin Metallurgical Plant (Huta Szczecin), whose large customer was this shipbuilding plant, ceased their production. Ship repairs have plummeted. In the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, unlike the Pomeranian one, new economic sectors are developing extremely slowly. The interior of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship reports a decline in the rural population. The population is “drawn” to the main cities of the voivodeship — Szczecin, Koszalin and Swinoujscie.

The Silesian Voivodeship is a classic example of a depressed old industrial area. Most of the population and economic life of the voivodeship concentrates in the Upper Silesian Industrial Region (Pol. Górnośląski Okręg Przemysłowy, GOP), established mostly during the time of the Polish People’s Republic, with a population of approximately 2 million. This industrial area is the largest city in Poland, as its member cities (Katowice, Sosnowiec, Ruda Slaska, Zabrze, Chorzow, etc.) merged long ago. The specialization is typical for old-industrial areas: coal mining, metallurgy, coke production, and resource-intensive engineering. This explains the depression in the Silesian Voivodeship. It seems impossible to fully accept Popov’s assertion that “during the post-socialist period the Silesian Voivodeship became one of the most striking examples of effective regional development supported by European subsidiarity programs” [21, p. 72]. If this were true, both the total voivodeship’s and its principal city’s populations would grow, not shrink.

The depression in the Łódź Voivodeship is associated with the degradation of light industries, mainly textiles, as well as leather and footwear industries. In the Russian Empire, Lodz was the major centre of the textile industry, the fifth most populous city after St. Petersburg, Moscow, Warsaw and Odessa (314,000 people according to the 1897 census). The industrial development of Lodz in the second half of the 20th century was determined by its orientation to the Comecon markets, mainly the USSR. At the end of the 20th century, Lodz lost this market, which ruined the light industry in the city and the voivodeship.

In the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, the demographic situation in Bydgoszcz, where the main city-forming enterprises, for example, PESA (Pojazdy Szynowe Pesa Bydgoszcz, production and repair of locomotives, wagons and trams), have existed since German times, is more difficult than in Torun. Most of Torun’s enterprises were created during the PRL, for example, the Torun Dressing Plant (Toruńskie Zakłady Materiałów Opatrunkowych producing a wide range of sanitary and hygienic products), built in the 1950s as a plant of the Ministry of National Defense of the Polish People’s Republic.

Three of the four “backward” voivodeships (Warmian-Masurian, Podlaskie and Lublin) are located along the Polish border with Russia, Lithuania, Belarus and partly Ukraine. Their relatively slow socioeconomic development can be attributed to the peculiarities of Poland’s eastern border development. In pre-revolutionary times, when Warsaw was the third city of the Russian Empire, its sphere of influence extended to the territory of then Russia, including modern Lithuania and western Belarus — Vilna (Vilnius), Grodno, Brest-Litovsk (Brest). In the interwar period, the current Western Ukraine (Lviv) fell within this sphere. With the Soviet annexation of Western Belarus and Western Ukraine in 1939 and the incorporation of the Lithuanian SSR into the Soviet Union in 1940 [22], the eastern regions of present-day Poland were left without major “organizing centres”, although some of them were returned to Poland in 1944 (the Bialystok region of the BSSR together with Bialystok [23]) and 1945 (from the Ukrainian SSR, the city of Przemysl with the adjacent territory, present-day Przemysl in the south-east of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship). Secondary cities took the place of the lost “organizing centres”. For the present Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, which constituted a part of Germany before World War II, due to its geographical location (wide access to the Vistula Bay), the main “organizing centre” was Königsberg, present-day Kaliningrad.

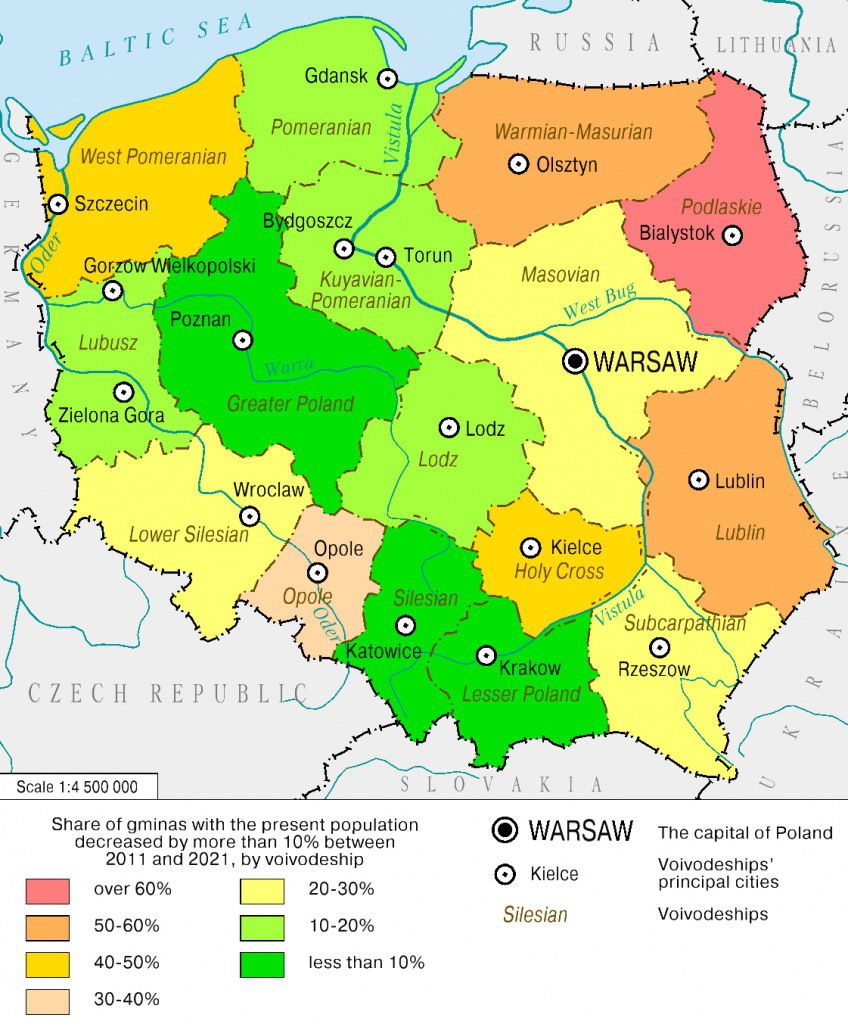

Until the early 21st century, the eastern voivodeships had been developing more slowly than Poland in general, but still developing. However, with the introduction of a visa regime between Poland, having joined the Schengen zone, and Russia and Belarus the already established cross-border ties began to break up. This was predictable, but the Polish government took no measures to prevent it or minimize its consequences. As noted in 2009, “Polish politicians were so absorbed in joining the EU that few people thought about developing an effective regulatory system for the period after 2004. …The policy documents of the voivodeships on regional policy are largely formal...” [25, p. 76]. With the PiS government coming to power, there was an increasing number of severed ties. Some Polish sources call the country’s eastern border the “eastern wall”. In the Podlaskie Voivodeship, bordering Lithuania and Belarus, in the inter-census period (2011—2021), the population decreased by more than 10 % in about 60 % of its gminas. Only the gminas around Bialystok and Lomzu, the second principal city of the voivodeship, find themselves in a more favourable demographic situation (Fig. 3).

In the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, which shares a border only with Russia, over half of the gminas experienced a population decline of more than 10 %. In the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, in addition to the regions bordering the principal cities of Olsztyn and Elblag, there are several gminas that exhibit a relatively stable and healthy demographic situation. These gminas are located near the motorways connecting Olsztyn with Gdansk, Warsaw, and the Kaliningrad region. It is in these areas that the nascent Russian-Polish “cross-border regional formation” has started to become evident [26], [27]. However, the entire Braniewo County, where the Mamonowo-Braniewo, the main land Russian-Polish border crossing point, is located, suffered a population loss of more than 10 % between 2011 and 2021. In the post-socialist period, this county specialized in cross-border trade, colloquially called “shuttle trade”. Its plunge caused a decrease in living standards and out-migration.

In the Lublin Voivodeship, which shares borders with Belarus and Ukraine, over half of the gminas experienced a population decline of more than 10 %. However, there are gminas adjacent to the voivodeship’s main city of Lublin, as well as to major cities like Biala Podlaska, Chelm, and Zamosc, where a relatively favourable demographic situation persists. The border with Ukraine is much more “open” than that with Russia and Belarus: citizens of Ukraine have the right to visa-free entry into the Schengen zone and, thus, to Poland, but the “highway” of Ukrainian labour migration goes further south, through the Subcarpathian Voivodeship [28].

|

| 3 |

| Proportion of gminas with a decrease in resident population by more than 10% in 2011—2021, by voivodeship |

Compiled from: Ludność rezydująca — informacja o wynikach Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań, 2022, Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny, URL: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-rezydujaca-dane-nsp-2021,44,1.html (accessed 14.02.2023).

The Holy Cross Voivodeship, known as the fourth “backward” voivodeship, is marked by its economic and geographical location between Warsaw and Krakow. Between 2011 and 2021, the voivodeship faced a population decrease of more than 10 %, predominantly in the northern regions facing Warsaw and the southern regions facing Krakow. This trend is also noticeable in numerous gminas (administrative divisions) within the neighbouring Masovian Voivodeship, which shares a border with the Holy Cross Voivodeship to the north.

Conclusions

The 2021 census results indicate that Poland’s demographic profile is hardly favourable. The country generally goes through an ever-increasing demographic crisis. If the current trends persist for the next 20—30 years, this crisis can become a demographic catastrophe, and the negative trends will become irreversibleThe demographic policy implemented by the PiS Government, which aimed to increase the birth rate through financial incentives, did not yield significant results. In fact, it could be argued that this policy was unsuccessful. It is crucial to recognize that the birth rate and related factors are influenced more by public attitudes and prevailing demographic behavioural patterns than by specific demographic policies. These patterns and attitudes are shaped by society and cannot be radically changed by the state alone. This holds true not only for Poland but also for any other country, including Russia.

The only geodemographic region that has seen population growth in the inter-census period (2011—2021) is the Capital region, located in the centre of Poland. Warsaw ensures its development. The Coastal and Warta regions reported the smallest population decline. The main factor contributing to economic growth and thus to demographic stability in each of these regions is their economic-geographical position (Warsaw is Poland’s key transport hub, Gdansk and Gdynia are seaports, and Poznan and, in general, the Greater Poland are the places where the country’s major motorways intersect). Regions whose development largely relies on natural resources, as well as environmental conditions are losing their population. The creation of new industries and the reconstruction of existing ones cannot hamper this process.

The healthiest geodemographically and, accordingly, economically and socially geodemographic regions and voivodeships of Poland are those on the Vistula: the Lesser Polish Voivodeship (Krakow) in its upper reaches, the Masovian (Warsaw) in its middle reaches, the Pomeranian (Gdansk) in the lower reaches.

The communication environment framework provides a credible explanation for this, and it actually predicted it 20 years ago [30, p. 32]. Location within the Vistula basin, the “organizing axis” of the Polish state throughout its entire history, can be considered the determining factor in Poland’s spatial development. The Vistula axis can ensure the country’s healthy social and economic development in the foreseeable future. But this will require “pulling” most of Poland’s resources, including demographic ones, to the economic centres located along the Vistula. However, in many voivodeships, especially in the eastern ones, such resources are increasingly scarce. We can agree with the statement that “uneven distribution of the benefits of integration can lead to increased socio-economic imbalances (within Poland. — V. M., I. S.) and slow down national socio-economic development” [31, p. 58].

The geodemography of the old-industrial voivodeships (West Pomeranian, Lower Silesian, Silesian, Lodz, Kuyavo-Pomorsky) is quite peculiar. In some cases, it is possible to identify the economic and social causes of population decline in them clearly and easily, while in other areas of these voivodeships, geodemographic and socio-economic trends diverge. In the West Pomeranian, Kuyavian-Pomeranian and Lodz voivodeships, the reason for the decline in the population is their general economic decline. In the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, demographic deterioration is observed in both urban and rural areas, in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian and Lodz Voivodeships, it affects mainly cities, while the rural areas remain relatively stable. In the Silesian and Lower Silesian Voivodeships, rehabilitation of old enterprises and construction of new ones often lead not to an increase or at least a stabilization of the population but to its reduction. The increase in productivity due to the commissioning of new equipment reduces the need for labour, as a result, people leave prosperous and even economically dynamic cities and areas. The Lower Silesian city of Legnica is a clear illustration of this.

The eastern voivodeships (Warmian-Masurian, Podlaskie, Lublin), along with the Holy Cross Voivodeship in the central part of the country, are characterized by a challenging geodemographic situation. The primary factor influencing this situation is their economic-geographical location. The eastern voivodeships are on the border, the Holy Cross Voivodeship is between Warsaw and Krakow. The geodemography in the three “backward” eastern voivodeships cannot improve without a significant improvement in cross-border cooperation with Russia and Belarus. In present political realities, it is impossible to expect not only radical but even small improvements. Long before the current political events, Kuznetsov noted that “Poland has demonstrated the unfortunate influence of an ill-considered foreign policy based on historical fears on its economic connections with Russia” [32, p. 82]. Thus, the eastern voivodeships will continue to deteriorate demographically, economically, and socially. The “fight against the Russian threat”, which is the basis of the foreign policy of the current PiS government, creates more problems for Poland than for Russia. As strange as it may sound in the current situation, Poland is more interested in the destruction of its “eastern wall” than Russia and Belarus, although it keeps fortifying it.

In the poor voivodeships of Eastern Poland, more than anywhere else in the country, the spirit of the first Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth of Both Nations is preserved, expressed by the ancient motto of the Polish nobility “God, Honour, Fatherland”. The population of these voivodeships, especially the rural population, sees “Law and Justice” as the best defenders of law and justice. It is here that the geodemographic situation is very difficult. So difficult that soon the population decline can become massive. The consequences of this for the Polish state are unpredictable.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Gennady M. Fedorov, Professor, and the Director of the Centre for Geopolitical Studies of the Baltic Region at the IKBFU, for his invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article. His expertise and guidance have greatly contributed to the quality and accuracy of the content. The authors would also like to extend their thanks to Tatiana A. Andreeva, a senior lecturer at the Department of Cartography and Geoinformatics of the Institute of Earth Sciences at St. Petersburg State University. Her assistance in editing and designing the cartographic material has been instrumental in enhancing the visual representation of the article.