Estonian ‘Balticness’ as a social construct: meanings and contextual specifics

- DOI

- 10.5922/2079-8555-2023-1-3

- Pages

- 34-51

Abstract

This paper explores the Estonian vision of Baltic identity. Estonia’s authorities have repeatedly articulated their scepticism towards the concept of a stand-alone ‘Baltic region’ and the inclusion of Estonia in it, preferring to position their state as a Nordic country. Yet, in numerous cases, they have clearly labelled Estonia as a Baltic State. To identify the contexts and meanings labelling the country as a Baltic State, this contribution provides a content analysis of official speeches given by Estonia’s political leadership. It is concluded that, despite the visibility of socioeconomic issues in the discourse, the most comprehensive image of Estonian ‘Balticness’ is constructed by interconnected narratives built around the Soviet past and the ‘security threats’ associated with Russia. The theoretical framework of regionalism, which allows one to consider the Baltics as a social construct rather than a set of material factors, provides an additional explanatory model.

Reference

Introduction and literature review

The current literature on Baltic identity<1> offers up two main interpretations of the phenomenon. The first, positive one, highlights narratives such as strengthening the positioning of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as a progressive EU subregion and the inadmissibility of their marginalisation, distancing from the ‘negative’ image of post-soviet countries, joint efforts to increase the Baltic States’ influence in the international arena and particularly within the EU, forging interregional ties, etc. [1], [2], [3], [4]. The second, negative interpretation focuses on the period the countries spent as Soviet republics, which is perceived by the majority of national elites, the countries’ nationals and external observers as a heavy historical legacy [5], [6], [7], [8]. Here, the common past eclipses the meaningful differences between the three states and precludes alternative identities from taking root. The Estonian researcher Eiki Berg described a similar dichotomy fifteen years ago: ‘[t]he Baltic States have obtained both the image of the post-communist reform tigers or arrogant deserters from the Soviet past with their burdensome legacies’ [9, р. 49].

The negative interpretation of ‘Balticness’ certainly remains dominant. The Lithuanian scholar Mindaugas Jurkynas also comes to this conclusion, emphasising that today’s Baltic identity is ‘based on security concerns against Russia and Soviet legacies’ [10, р. 328], see also [11], [12].<2> These ‘concerns’ are, in turn, direct derivatives of the three countries’ historical relations with Russia.

The semantic associations produced by the negative interpretation of Baltic identity have serious implications for the political rhetoric in the three states. They prompt Baltic political elites towards embracing what might be called ‘identity escapism’, manifested in the ambition to classify the countries as part of more ‘prosperous’ regions. For instance, the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian leaders tend to position their states as Nordic countries [13], see also [14]. And they have achieved notable success in terms of international legitimation: in January 2017, the updated website of the UN Statistics Division categorised the three republics as Nordic states, much to the approval of Baltic politicians.<3>

Of all the three states, Estonia has the most articulated position in denying the existence of a ‘Baltic identity’. That is why the country was chosen for consideration in this study. Striving to provide a rationale for excluding their state from the Baltic region, Estonian politicians pursue two main narratives. The first one stresses the cultural and linguistic proximity of Estonia and the Nordic State of Finland. Today’s difference in living standards in the two countries is principally explained by Estonia having been part of the USSR for decades [15, р. 58—73], [16, р. 289]. The alternative narrative focuses on deliberate distancing from the image of a ‘post-Soviet country’, which might be evoked in the mind of an external observer confronted with the term ‘Baltic States’. Estonian politicians also emphasise that in some respects (sometimes very specific ones, such as popular knowledge of English or internet connection quality), Estonia is not inferior to the Nordic countries. These achievements are opposed to the possible negative associations relating to ‘Soviet legacies’, for example, corruption [17, р. 192—193], [18, р. 356].

After independence, a prominent advocate of Estonia as a Northern European country was its minister of foreign affairs (1996—1998; 1999—2002) Toomas Ilves, who gave a seminal speech at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs on 14 December 1999:

Unfortunately, most if not all people outside Estonia talk about something called ‘The Baltics’.

I think it is time to do away with poorly fitting, externally imposed categories. It is time that we recognize that we are dealing with three very different countries in the Baltic area, with completely different affinities. There is no Baltic identity with a common culture, language group, religious tradition.<4>

Instead of the Baltics, Ilves proposed to relate Estonia’s regional identity to the so-called Yule-land, whose concept he outlined in the same speech. He saw this region as comprising all the countries where the mid-winter festival of Yule is traditionally celebrated. Besides Estonia, these are the Scandinavian states (Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland) and the UK. The boundaries of Yule-land clearly coincide with some modern interpretations of the North European geographical area. In addition to the Yule tradition, Ilves saw as a unifying factor a mindset shared by Yule-land residents:

Brits, Scandinavians, Finns, and Estonians consider themselves rational, logical, unencumbered by emotional arguments; we are business-like, stubborn and hard-working. Our southern neighbours see us as too dry and serious, workaholics, lacking passion and joie de vivre.<5>

It appears that this message was spread in an attempt to grope for alternative ways to reinforce the image of Estonia as part of Northern Europe: if Yule-land is viewed from the perspective of economic performance and living standards, the difference between Estonia and the other states would be too apparent. Although Ilves’s concept did not gain wide currency, it did contribute to legitimating Estonia’s Northern European identity. Aldis Purs notes that few observers ‘register[ed] Ilves’s attempts at humour within the speech’, but ‘[h]is suggestion ... set off a long-lasting debate’ [6, р. 10].

Interestingly, if one pursues a closer investigation of the Estonian leadership’s political rhetoric, the identity escapism discussed above will lead them into a paradox: if the Baltics do not exist as a single entity, why does Ilves, just like many other Estonian speakers, associate his country with the correspondent region? For example, in the speech quoted above, he states: ‘what the three Baltic States have in common almost completely derives from shared unhappy experiences imposed upon us from outside: occupations, deportations, annexation, sovietization, collectivization, russification’.<6> Later, during his term in office as president (2006—2016), Ilves spoke of the struggle of the ‘three Baltic musketeers’ for freedom,<7> the ‘Baltic’ peoples’ striving for independence,<8> the intellectual and geographical proximity of the ‘Baltic States’,<9> not to mention many other contexts where the three republics were treated as elements of a single whole.

The present work aims to explore this paradox and identify the contextual features of the positioning of Estonia as a Baltic State by the country’s leadership. The findings may contribute to a better understanding of Estonian politics by answering the question as to why, despite the repeatedly articulated desire to get rid of the Baltic ‘label’, the latter retains a prominent place in national discourse.

The article is composed of five sections. The first one is an introduction and literature review. The second one analyses in line with the research objective how the concept of the region evolved in academic discourse and how it is operationalised. The third section outlines the methodology of the study. The fourth one describes and interprets the findings obtained. The fifth section contains final conclusions.

The region: the evolution of the concept and the operationalisation of the notion

A possible reason behind the paradox is that the very term ‘region’ can be operationalised in different ways. When speaking of the absence of Baltic identity, Ilves emphasises its constituent material elements: culture, religion and language.<10> On the other hand, he mentions in the same statement the ‘shared unhappy experiences’ of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, acknowledging the existence of non-material unifying factors, such as episodes of a common history.

Setting the two in opposition, Ilves concludes that the Baltic States are too different in material terms to be legitimately classified as a single region. Academic science, however, views this approach as obsolete. As an analytical category, the region is defined not through counterpoising material factors with non-material ones but rather through amalgamating them as operational components of the notion. Peter Katzenstein formulates this as follows:

They [regions] are more than the flow of goods and people across physical space that we can assume to be represented directly and accurately by cartographic depictions. Regions are also social and cognitive constructs that are rooted in daily practice [19, р. 129].

A more tangible nature of material facts and the ensuing simplicity of corresponding analysis made them first-priority objects for research. Such a focus was characteristic of traditional regional geography.<11>

A prime example is the work by the British researcher Peter Hagget Locational analysis in human geography. He links the fact of the existence of a region to ‘successive demarcation of regional cores and boundaries’ [22, р. 254], which covers a range of variables subject to measurement and comparison: climate, landscape, economic development, etc.

Hagget, like other followers of the traditional school, saw regions as a part of objective reality that can be identified through analytical work.<12> Yet, they paid little attention to the regions that are ‘recognized informally, almost intuitively’, such as historical regions. Hagget called such regions ‘instinctively appropriate’, emphasising that ‘they remain distinct only when viewed from a distance — on close examination they dissolve into a new series of still smaller “character areas”’ [22, р. 245].

This positivistic approach was exceptionally vulnerable to criticism because of its limited heuristic value. For instance, George Kimble criticised exponents of traditional regional geography, likening their work to attempts ‘to put boundaries that do not exist around areas that do not matter’, stressing that ‘the whole life of a given area is greater than the sum of all the measurable parts, whether dynamic or static’ [22, р. 241]. Although Hagget acknowledged the problem, he never provided a substantial response to the criticism. He wrote that regions ‘continue to be one of the most logical and satisfactory ways of organizing geographical information’ [22, р. 241].

This thesis could be perceived only as an invitation to further debate. An important contribution was made by scholars of the Marxist school who established a direct connection between regionalisation and capital allocation.<13> A remarkable proponent of this school of thought was the founding father of the world-system theory, Immanuel Wallerstein, who proposed the division of geographical space into core, periphery and semi-periphery according to the established capitalist relations [27].

A major breakthrough in regional geography was made with the development of the constructivist approach, whose followers created a new school of regional geography.<14> It abandoned the perception of regions as elements of objective reality for exploring the driving forces behind their emergence and transformations. In other words, constructivists focused not so much on regions as on the processes affecting region building and evolution. The Belgian researcher Luk Van Langenhove describes this peculiarity as follows: ‘region building is always a process. Regions are not constructed overnight: it is a step-by-step sequence with its own internal dynamics and a broad set of geopolitical and economic factors’ [28, р. 318]. This approach was vastly different from the concept adopted by the traditional school, whose advocates believed that regions should be identified based on formal properties.

Nevertheless, it would not be entirely accurate to say that proponents of the new school completely denied the role of material factors and focused exclusively on issues such as the dynamics of regional discourses and social practices. On the contrary, their works demonstrated a willingness to combine material and non-material categories in a proportion such as to solve the research problems tackled. Hence the interest in creating integrated models reflecting the process of region building. The most advanced model to date is the ‘institutionalisation of regions’ proposed by the Finnish scholar Anssi Paasi [29], see also [30], [31].

His model depicts the process of region building as consisting of four stages: the assumption of a territorial shape, the formation of symbols, the formation of institutions and, finally, functioning. These stages do not necessarily follow in this order: the order can be random, or some of these processes may occur simultaneously. The assumption of a territorial shape means the emergence of a finite space held together by common features, which may result from a historical process or be ad hoc. In their turn, the boundaries of such a space can be either ‘rigid’ (established administratively) or ‘blurred’ (drawn according to natural or landscape features, cultural considerations, ethnic stereotypes, etc.).

Symbol formation involves the creation of meaning-laden images expressing and reinforcing regional identity. One of the central symbols is the name of the region: when pronounced, it has to summon up a certain comprehensive image in the minds of the locals and external observers alike. Another symbol is local toponymy, which may be reminiscent of a shared past or distinguish members of a group.

The formation of institutions consists in building various functional constructs merging the region into a cohesive whole. These include formal institutions, regional organisations and associations, on the one hand, and informal practices, such as habits common in the local population or some specific attitudes, on the other.

Finally, the functioning of a region means that it becomes part of the global space and collective consciousness. Functioning regions enter into a struggle for resources and power, and their names repeatedly occur in various discourses and social practices relating to politics, the economy, mass communications, culture and education.

According to Paasi’s model, the willingness of politicians to articulate the name of a region may be sufficient evidence of its functioning as an element of the world system. This circumstance points to the presence of a Baltics-centred context, which, when evoked, seems to encourage Estonian politicians to ‘abandon’ their ‘primal’ Nordic identity and position Estonia as a Baltic State. To describe this context and the specifics of such positioning, the author proposes to employ the methodology of content analysis.

Methodology

This work applies content analysis to official statements made by the presidents, prime ministers and ministers of foreign affairs of the Republic of Estonia between 1 March 2011 and 1 March 2021.<15> This choice was informed by the consideration that the politicians holding these offices convey the nuances of Estonian regional identity, on the one hand, and construct it in their capacity of agents, on the other.<16> Their official statements are important sources providing a visual picture of identity ideas held by both the Estonian national elite and, with certain reservations, Estonian society.

With a view to high-quality research and in an attempt to avoid distortions produced by translation, it was decided to use texts of official statements in the Estonian language whenever available. Otherwise, English texts were analysed. The corpus was compiled manually,<17> with three categories covered. The first category comprises the texts of official statements with at least one occurrence of a word with the root balti, its derivative<18> or a related form.<19> The second one includes actual episodes of usage of these lexical items, i. e. each individual occurrence in the text of an official statement. Within the text fragments (paragraphs),<20> the keywords were identified that gave insight into the context.<21> The third category was compiled by extracting from the first category text phrases, compound words and abbreviations formed from the root balti.

This approach to corpus formation was chosen because the Estonian words derived from this root are linked semantically to the Baltic States (Estonian Baltimaad). Pärtel Piirimäe of the University of Tartu notes that, in Estonian, the word Baltimaad is used in a very narrow sense, namely, to refer to the Baltic States – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, while the Estonian term for the Baltic Sea region states is Läänemeremaad (literally, countries of the Western Sea) [5, р. 67]. Presumably, the word Baltimaad comes from the German name for the region, Baltikum. This theory is supported by the fact that Baltikum is sometimes used in Estonian in the same sense.

In German, however, the meaning of the term Baltikum changed over time. At first, it was used to refer to the area populated by Baltic Germans, which is now part of Estonia and Latvia. During World War I, its meaning expanded to include all the north-western territories of the Russian Empire occupied by the troops of the German Empire. And the word acquired its current meaning only after World War II.<22>

The contexts where words derived from the root balti are used were divided into four categories: socioeconomic issues, politics and political history, defence and security, and science, culture and education. An occurrence was assumed to belong to a certain contextual category if the surrounding context contained correspondent keywords.

The keywords for the category ‘socioeconomic problems’ were as follows:

— economy (Estonian: majandus), human development (Estonian: inimareng), finance (Estonian: finants, rahandus), market (Estonian: turg), transport infrastructure (Estonian: transporditaristu), integration (Estonian: lõimimine), rail (meaning Rail Baltic), energy (Estonian: energia), innovation (Estonian: innovatsioon), digital (Estonian: digitaal), social (Estonian: sotsiaalne), workforce (Estonian: tööjõud), nature/environment (Estonian: loodus), pipeline (Estonian: torustik), oil shale industry (Estonian: põlevkivitööstus), well-being (Estonian: heaolu), business, investment (Estonian: investeeringud).

The keywords for the category ‘politics and political history’ included:

— Soviet (Estonian: nõukogude), totalitarianism (Estonian: totalitaarsus), freedom (Estonian: vabadus), independence (Estonian: iseseisvus), occupation (Estonian: okupatsioon), authoritarianism (Estonian: autoritaarsus), values (Estonian: väärtused), history (Estonian: ajalugu), Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (Estonian: Molotovi — Ribbentropi pakt), communism (Estonian: kommunism), Cold War (Estonian: külm sõda), repressions (Estonian: repressioonid), chain (Estonian: kett; meaning the Baltic Chain, Estonian: Balti kett<23>), appeal (Estonian: apell; meaning the Baltic Appeal, Estonian: Balti apell<24>), identity (Estonian: identiteet).

Amongst the keywords for the category ‘defence and security’ were:

— defence (Estonian: kaitse), NATO (Estonian: NATO), security (Estonian: julgeolek), ally (Estonian: liitlane), attack (Estonian: rünnak), airspace (Estonian: õhuruum), armed forces (Estonian: relvajõud), aggression (Estonian: agressioon), deterrence (Estonian: heidutus), invasion (Estonian: sissetung).

Finally, the keywords for the category ‘science, culture and education were:

— education (Estonian: haridus), literature (Estonian: kirjandus), language (Estonian: keel), culture (Estonian: kultuur), theatre (Estonian: teater), (an) intellectual (Estonian: intellektuaal), festival (Estonian: pidu), science (Estonian: teadus), research (Estonian: uuring).

The method chosen for corpus formation has a number of limitations: some of the words coming from the root balti are used to refer to geographical areas beyond the Baltic States. The most obvious example in the study sample is the term Nordic-Baltic countries (Estonian: Pohja-Balti ruum, Balti-Põhjala piirkond, etc.), which denotes the three Baltic States and five Northern European countries: Iceland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Finland. Moreover, some of these words are used to refer to physical entities located partially or even completely beyond the territory of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. For instance, the Balticconnector is the gas pipeline between Estonia and Finland. The railways of Rail Baltic are planned to run across Finland and Poland; the project also includes an undersea tunnel under the Gulf of Finland.

Nevertheless, excluding these occurrences from the study will unreasonably complicate the research methodology. Based on this consideration, no additional conditions were introduced, and the units of analysis were selected according to the above rule for the occurrences of words coming from the root balti.

Results

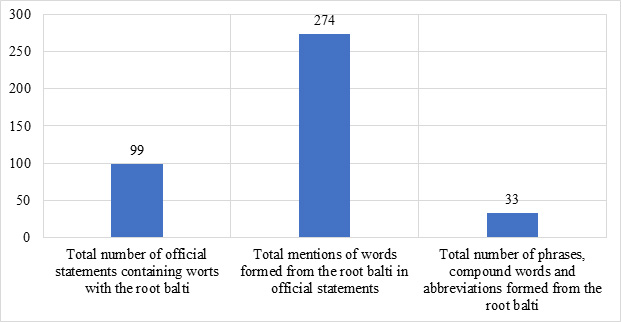

Between 1 March 2011 and 1 march 2021, Estonian presidents, prime minister and ministers of foreign affairs made 99 statements that had at least one occurrence of a word coming from the root balti, its derivative or a related form; there were 274 total occurrences of such words and 33 of phrases, compounds and abbreviations containing the root balti (Fig. 1).

|

| 1 |

| Structure of the study corpus |

|

Source: here and below, calculated by the author based on data available on the official websites of the President of Estonia, the Government of Estonia and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Estonia.<25> |

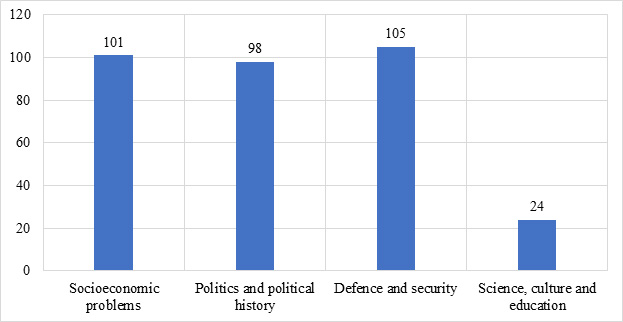

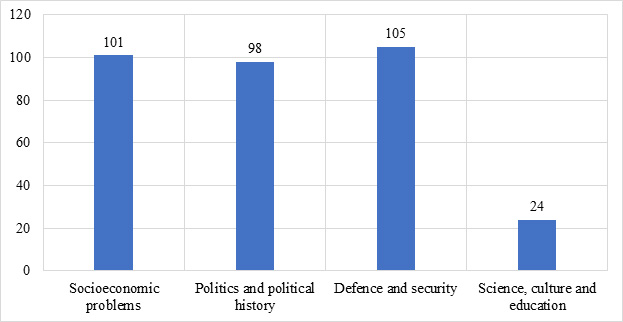

Fig. 2 shows the distribution of the occurrences across contextual categories in absolute numbers; Fig. 3, in percentage terms, rounded to an integer. Since a single paragraph may contain keywords from several contextual categories, the number of categorised occurrences was greater than the number of occurrences in the sample (Fig. 1).

|

| 2 |

|

Distribution of occurrences of words containing the root balti across contextual categories, absolute numbers |

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

Distribution of occurrences of words formed from the root balti across contextual categories, relative values

|

|

|

The table shows various phrases, compound words and abbreviations formed from the root balti. The number of occurrences in all the official statements made over the study period is provided for each lexical item.

A list of phrases, compound words and abbreviations formed from the root balti and occurring in the study corpu

|

Baltic States / the Baltics (Estonian: Balti riigid/Balti piirkond, Baltimaad, Baltikum, Balti regioon) |

104 |

|

Baltic Chain / Baltic Way (Estonian: Balti kett) |

26 |

|

Rail Baltic |

23 |

|

Baltic cooperation/cooperation of the Baltic States (Estonian: Balti riikide koostöö) |

17 |

|

Baltic Appeal (Estonian: Balti apell) |

16 |

|

Nordic-Baltic region (Estonian: Balti-Põhjala piirkond, Põhja- ja Baltimaad) |

15 |

|

Nordic-Baltic cooperation (Estonian: Põhja-Balti koostöö, Balti- ja Põhjamaade koostöö) |

12 |

|

Baltic air-policing mission (Estonian: Balti õhuturbemission and similar expressions) |

12 |

|

Baltic Germans (Estonian: Baltisakslased) |

6 |

|

Baltic States’ airspace (Estonian: Balti riikide õhuruum) |

5 |

|

Balticconnector<26> |

5 |

|

Baltic Defence College (Estonian: Balti Kaitsekolledž) |

4 |

|

Baltic energy system / Baltic power grid (Estonian: Balti energiasüsteem / Balti riikide elektrivõrgud) |

4 |

|

Baltic peoples (Estonian: Balti rahvad) |

3 |

|

Baltic Assembly (Estonian: Balti Assamblee) |

2 |

|

Baltic-Polish region (Estonian: Balti-Poola regioon) |

2 |

|

Baltic Council of Ministers (Estonian: Balti Ministrite Nõukogu) |

2 |

|

NordBalt<27> |

1 |

|

Baltic–Nordic economic ties (Estonian: Põhja-Balti majandussuhted) |

1 |

|

Stockholm Baltic Archives (Estonian: Balti Arhiiv Stockholmis) |

1 |

|

Baltic digital sandbox (Estonian: Balti digi-liivakast kokku) |

1 |

|

Baltic musketeers (Estonian: Balti musketärid) |

1 |

|

Baltic neighbours (Estonian: Balti naabrid) |

1 |

|

Baltic Teachers’ Seminar (Estonian: Balti Õpetajate Seminar) |

1 |

|

Baltic barons (Estonian: Balti parunid) |

1 |

|

Baltic regional liquid natural gas terminal (Estonian: Balti regionaalne veedeldatud gaasi terminal) |

1 |

|

Baltic Ghost<28> |

1 |

|

Baltic units |

1 |

|

Baltic Workboats<29> |

1 |

|

Baltic grain processor (Estonian: Baltimaade teraviljatöötleja) |

1 |

|

Baltoscandia (Estonian: Baltoskandia) |

1 |

|

NATO’s Baltic wing (Estonian: NATO Balti-tiib) |

1 |

|

Nordic and Baltic neighbours (Estonian: Põhjala ja Balti naabrid) |

1 |

|

Total occurrences |

274 |

The data obtained from content analysis lead one to several conclusions. As Figs. 2 and 3 show, the categories ‘socioeconomic issues’, ‘politics and political history’ and ‘defence and security’ are almost equally represented in Estonia’s ‘Baltic discourse’. Yet, their contribution to the construction of the Estonian vision of Baltic identity differs. There is a close narrative connection between the categories ‘politics and political history’ and ‘defence and security’. A considerable share of statements in these groups focuses simultaneously on two narratives: the Baltics as ‘victims of Soviet occupation’, on the one hand, and Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as the ‘eastern outpost of Europe, NATO and, in some cases, the entire Western civilisation protecting them from the “Russian threat”’, on the other. The latter seems to follow from the former, thus constructing the single logic behind this argumentation, which may be outlined as follows: ‘having had a “traumatic experience” of dealing with the USSR, the Baltic States desperately need to cooperate with the West to strengthen defence and security in the face of Russia’.

This logic supports Jurkynas’s thesis cited in the first section of this article that it is the Soviet legacy and security concerns over Russia that underpin the current Baltic identity. From the Estonian perspective, this statement is absolutely justified. However, one should not overlook the fact that the category ‘socioeconomic issues’ is also highly visible in the study discourse. The statements by Estonia’s political leadership point to considerable interest in regional cooperation towards stronger international trade in the Baltics, the region’s attractiveness to investors, a modernised transport infrastructure and closer partnership in information technology. The socioeconomic category includes many elements, and none is overwhelmingly dominant. Yet, there is a sharp focus on energy security, which has a clear semantic connection to ‘defence and security’. Remarkably, Estonia is often placed in opposition to Latvia and Lithuania as a state that has achieved greater socioeconomic success since independence. It is implied that this success supports Estonia’s claim to the status of a Nordic country, particularly in comparison with Lithuania, which Estonian politicians sometimes classify as an Eastern European country.

The category ‘science, culture and education’ is the least visible within the discourse. The small number of occurrences in this contextual category disproves the thesis about the Baltics comprising a single cultural and academic space. The situation is complicated by some important aspects of cultural cooperation being left out, for obvious reasons, of the scope of the official statements (for example, collaborations between the Russian theatres in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania).

Finally, it is worth noting the barren institutional and symbolic landscape of the Estonian version of Baltic identity. As can be seen, phrases, compounds and abbreviations coming from the root balti are used by Estonian politicians mostly to refer either to episodes of the shared Baltic history of the Soviet period (Baltic Chain, Baltic Appeal) or current defence and security problems (Baltic air-policing). The only notable phrase that occurs in a different context is Rail Baltic. However, the project carrying this name has experienced so many delays that it can be considered discontinued and most of its positive symbolic potential nullified.

Interestingly, trilateral Baltic institutions, such as the Baltic Assembly and the Baltic Council of Ministers, had the fewest mentions in the statements of Estonian politicians. Therefore, little significance is attached to these institutions in practical political terms, which supports Vladimir Olenchenko and Nikolai Mezhevich’s conclusion that these organisations have to do more with protocol than anything else [34, p. 34] and Olga Konevskikh’s definition of the Baltic Assembly as ‘another venue where representatives of the three countries can meet rather than a powerhouse shaping the common policy of the member states’ [35, p. 58].

Conclusion

This study has shown that Estonia’s Baltic identity manifests itself most coherently in a combination of interwoven narratives relating to security and the Soviet legacy. Together, they account for most of the context where the Estonian political leadership is likely to abandon labelling their country as a Nordic state and change the focus to its Baltic identity. This shift has a value-based and instrumental motivation. On the one hand, the stigmatisation of the ‘Soviet legacy’ is an essential element of national identity reinforcement, readily accepted by the local population and external observers alike. On the other, it contributes to the reputation of the Baltic States as ‘experts on Russia’, which provides substantial benefits: the three countries are playing an increasingly important part in framing the EU’s policy towards Moscow. In Estonia’s ‘Baltic discourse’, Russia has the role of ‘the other’, the principal object of security concerns. The latter consideration indicates that the study discourse is highly securitised.

This research and its findings cannot be considered an exhaustive description of the Estonian vision of Baltic identity. Although the political elite actively participates in constructing the country’s regional identity, it is not the only actor in the process. Further work needs to be done to analyse national media discourse, educational practices, documented political doctrines and public opinion.<30> Investigating the discourse of the Latvian and Lithuanian political elites would be an important contribution to a comprehensive study of Baltic identity. These discourses are expected to have much in common with their Estonian counterpart while possessing some unique characteristics.

The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation within project № 20-78-10159 The Phenomenon of Strategic Culture in World Politics: Specifics of Influence on Security Policy (On the Example of the States of the Scandinavian-Baltic Region).

Acknowledgements

The author expresses his deepest gratitude for assistance in preparing this work to Mikhail Berezin, first-year master’s student of the School of International Relations at MGIMO University, Dr Vladislav Vorotnikov, director of the Center for European Studies of the Institute for International Studies at MGIMO University, Dr Anastasia Volodina, senior lecturer of the Department of North European and Baltic languages at MGIMO University, Dr Igor Okunev, director of the Center for Spatial Analysis in International Relations of the Institute for International Studies at MGIMO University, and Nikita Neklyudov, lecturer at the Department of Applied International Analysis at MGIMO University.

The author also would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which contributed to the improvement of the study.